Is contemporary street photography art or documentary?

This thesis seeks to explore the discipline of modern street photography.

Andrey Belov-Belikov

Street photography experiences a skyrocketed popularity nowadays, due to its very loose and free nature, as this is the genre which does not limit with any concrete guidelines. In addition to that, this discipline has a long, as old as photography itself, and complicated history, during which we can observe the complex relations with documentary and photojournalism.

This is the first article in our series of master theses.

This thesis seeks to explore the discipline of modern street photography and how it is featured by means social networks and photo-sharing websites. The objective of the thesis is to figure out how the ubiquity of digital devices (mobile phones in particular) influences the development of street photography. The thesis aims to distinguish the major trends or sub-genres of modern street photography and to find their placement on the scale between Art and Documentary, in the context of the ubiquity of digital photography. This is an extract of the original Master’s Thesis Master in digital communication and culture 2017, Inland University of Applied Science, Norway.

The history of street photography

Street photography is the genre that, we might say, is as old as the medium of photography itself. The essence of what is known now as ‘street photography’ is “the impulse to take candid pictures in the stream of everyday life” (Howarth, McLaren, 2012, p. 9). According to the authors, street photography is an ‘unbroken tradition’, leading back to the invention of photography per se. What they mean is that the very first photographic images ever taken come under the notion of street photography, because most of the pictures in the early days of photography were taken on the streets, hence they fulfil the major criteria of being the street. An example is the picture of Nicéphore Niepce (1826), the oldest preserved photographic image in history, which depicts the view from the window in France, and qualifies as a street photograph.

The origins of street photography coincide in time with the beginning of globalization processes in the late nineteenth century. Rapid urbanization in Europe and the United States inspired the technological development, which in turn gave momentum to the artistic techniques and ideas, that had to be featured, therefore street photography, being urban by default, was present in the right place at the right time.

The photographic movements all over the world at the beginning of the XX century (in Russia, the US, Britain and France) were pushed initially by social documentary, which sets sights on the illustration of the real world and the real people in private and social conditions. Bate describes social documentary as the movement that “was emphatically about constructing the idea of a public realm through social experience”. However, it does not indicate the function of the photograph as a document (Bate, 2016, p. 73).

As exemplified by Howarth and McLaren, street photography today has been gaining extreme popularity. Flickr, the world's biggest photo-sharing website, contains more than 400 groups devoted to street photography. So-called “home of street photography” website, In-Public, counts up to 100000 hits a month. Universities and museums now offer courses in the history and practice of street photography, and increasing interest in citizen photojournalism has opened new online editorial opportunities for photographers to display their work. It is important to note that young photographers are interested in depicting the cities of the developing world (Howarth McLaren, 2010, p. 15). This is what concerns contemporary street photography conditions, governed basically by the digital revolution, and the way how candidness of street photography ideally coincided with the mobility of digital devices. Notwithstanding, the disputes on the modern status of street photography cannot be provided without the observing of its history.

Lewis Hine

When it comes to a historical understanding of the medium of general photography it is necessary to mention Lewis Hine, a documentarian who at the beginning of XX century saw the art photography as the way to capture real life, whilst camera was seen as a tool to present empirical evidence of something happened (Hine, 1909, pp. 355-59). However, Trachtenberg elaborates, saying that it does not necessarily mean any beauty or personal expression, but just a picture of how people live (Trachtenberg, 1981, p. 240). This idea of Trachtenberg relates to street photography quite tight, as it does not strike for the glamorous depiction, but rather for the instant picture as it is.

Wells suggests there is a tradition of street photography that was formed by the historical images from the streets that were a “mainstay of photographic practice” (2015, p. 118). This tradition was defined by Westerbeck and Meyerowitz as “candid pictures of everyday life in the street”, to which they also include such public places as bars, cafes, parks etc. (1994, p. 34-35). Which in my opinion is a too broad definition and may include all kinds of nuances.

“I believe that street photography is central to the issue of photography - that it is purely photographic, whereas the other genres, such as landscape and portrait photography, are a little more applied, more mixed in with the history of painting and other art forms (Meyerowitz, in Salkeld, 2013, p. 87).

Payment Failed

Henri Cartier-Bresson and the decisive moment

There is no much of a dispute on a subject of the birthplace of the genre because Paris was always considered as a dominant city in the early history of street photography, not only because it was strongly influenced by the development of modernity and urbanism, but also due to appearance of department stores, tabloid newspapers and other forms of press. And the photographers who are now considered to be the greatest figures in the medium of all time, all started in Paris back in the 1920s and 1930s, these are Robert Doisneau, Willy Ronis, Brassai, Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson (Wells, 2015, p. 119). Here is the first I ought to mention the name of one of the greatest personalities in the history of photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson, which is unavoidable in the street photography discussions. Not only his matchless photographic style made a significant impact on the further artists' development but the defined key concept of street photography serves as a major guideline for photographers all over the world. His idea of the “decisive moment” is a well-seen demonstration of expressive realism in social documentary. It represents the fusion of momentary in the photograph with the old art history concept of telling a story with the help of one picture (Bate, 2016, p. 79).

Warren refers to Cartier-Bresson and the way he applied the “decisive moment” concept: it answers to an essentially modern urban condition: only the metropolis contains such a vast amount of chance encounters and only the modern urbanite, who has interiorized the shock experiences of modernity, is capable of making necessary fast and immediate reactions. Cartier-Bresson combined these quick reflexes with a gracious elegance.” (L. Warren, 2007, p. 1504).

Cartier-Bresson himself explains the concept as “one unique picture whose composition possesses such vigour and richness, and whose content so radiates outward from it, that this single picture is a whole story itself.” (Bate, 2016, p. 80).

John Szarkowski formulated his iconic theory of photography regarding the aspects of production and outcome related to artists of different backgrounds and practices, while still obeying the previously established rules and critically distinguishing new photographers on the ground of several formal principles (Sampson, 2007, p. 232). These are five elements that must be acknowledged by the artist to transform the “actual” world into a “picture”: “the thing itself”, “the detail”, “the frame”, “time” and “vantage point”. Especially, Szarkowski emphasizes on the element of “time”, tying it to the concept of decisive moment by stating “decisive, not because of the exterior event (the bat meeting the ball) but because at that moment, the flux of changing forms and patterns was sensed to have achieved balance and clarity and order – because the image became, for an instant, a picture” (Szarkowski, 1966, p. 7). To put it bluntly, Cartier-Bresson refers to the visual culmination, not a dramatic one, so that the image that counts not a story.

Robert Frank

In the post-war world, to be precise, in the 1950s we can witness the dramatic cultural changes in the dominance of Paris in favour of the USA, and New-York in particular, which reflected on street photography establishment, bringing in the new names and new styles. The brand-new photographic trends were entrenched, expanding the horizons of photography approaches. The most recognized personalities of the US street photography are Robert Frank, Joel Meyerowitz, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand and many others (Wells, 2015, p. 119).

Another wave of establishing the genre of street photography (after Henri Cartier- Bresson and other Parisians) is tied to the name of Robert Frank and his infamous work The Americans, published in 1958, became a major photo-essay of the 1950s, where he offered his vision of American life and held back documentary approach, but applied more ironic one, showing the moments of America's ordinary life. What is significant in this photo work is that he, being Swiss, showed America from an alien's point of view, as an outsider. Thus, we can recognize not only honesty but also objectivity towards the depicted. People on his photographs are not poor or any other particular kind of social being, but as Wells describes them, they exist as spectators looking at some invisible scene, which does not contain anything of great importance. Frank refused to show productive industrial life of America full of economic success as in some documentary project, he instead expresses the idea that most of the events happening every day do not have any special meaning, while some of them can become special just by being photographed. Frank himself tells “to produce an authentic contemporary document, the visual impact should be such as will nullify explanation.” (Sontag, 2005, p. 86).

Concerning his views on documentation of his work, when applying for Guggenheim Fellowship Frank writes “it is only partly documentary in nature: one of its aims is more artistic than the word documentary implies” (Tucker, 1986, p. 94). Frank himself did not mean to document American life in the way his predecessors had been doing it, as he rather applied his artistic skills and the brand-new approach to the content and the subjects of his photography. As a result, he created a very controversial, yet to a great extent influential piece of art, which was also considered as a depiction of the dark side of American life. Wells, therefore, states the fact and underlines that “the subject matter of documentary is both dispersed and expanded to include whatever engages or fascinates the photographer. Facts now matter less than appearances”. Frank's job became an indicator of the shift documentary photography was experiencing. It was a shift of tone towards subjectiveness, identities and pleasures (Wells, 2015, p. 121). Furthermore, Frank's work coincided in time with the revolutionary social changes (civil rights protests, student uprising, forthcoming sexual revolution etc.). He was on those who gave momentum to the street photography development throughout the whole half of XX century and even beyond (Bate, 2016, p.174), by applying his innovative approach to the visual of documentary.

Surrealism and its reflection in street photography

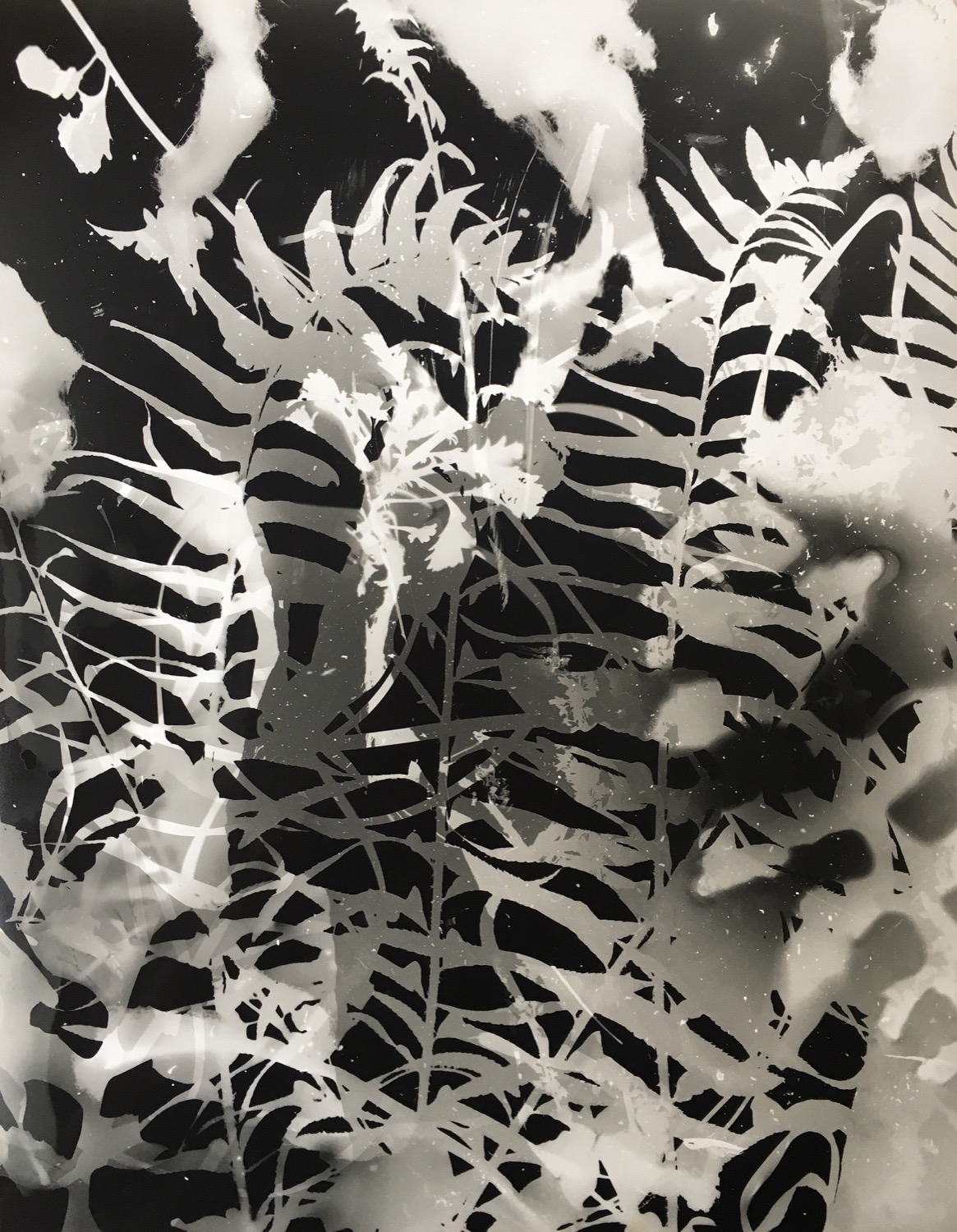

It is Stuart Franklin who finds the roots of street photography development in Surrealism as a phenomenon which had become the major impulse given to documentary street photography both in Europe and America to raise and develop from the 1920s until the 1970s and even beyond (Franklin, 2016, p. 153). Generally, photography as a medium can be defined as surreal, while street photography is a process which includes the ideal visual demonstration of the entire Surrealism concept. Apropos genius surrealistic expressions of Henri Cartier-Bresson's oeuvre, if we take Cartier-Bresson who is beyond all doubt the biggest figure in street photography, we can easily pick up the surrealistic scent in his works. Cartier-Bresson has always followed the rules of geometry while taking photographs. His pictures often include people but still are constructed on the principle of the golden ratio, thanks to Andre Lhote, the artist, who taught him and promote a love of geometry of the picture to.

Relations to documentary and photojournalism

David Blumenkrantz argues that, I would like to emphasize, historically street photography was holding a place in between Art and Documentary. In the most general sense, street photography might best be described as an exploration of urban life, with equal attention paid to human and environmental elements. It can be undertaken as a solitary, virtually anonymous venture, or one in which the photographer becomes known, and perhaps accepted as a temporary presence. Thus, from such descriptions and observation, it may seem that documentary does not differ from street photography whatsoever, due to their same intention to catch and interpret the reality, however, it must be noted that if documentary needs some general content of the scene and the exact location of the incident, then street photography does not require such settings. Also, a street photographer is not tied to time and can easily use the method of cut and try, whilst documentarian cannot afford such freedom. And one more point of difference is that the documentarian is seeking some social or political message he can transmit through the image, and street photographers are not hunting for any societal value.

On the contrary, there is a characteristic that separates street photographers from photojournalists, it is a lack of consideration for the traditional narrative. Street photographers work without any obligations or editorial restrictive guidelines which allows them to be subjective in interpretation. Kozloff continues on that subject “if these street photographers certify that nothing more is seen or meant than what is shown, they offer concrete findings without any journalistic pretext.” (1984, p. 69) But it does not mean that a street photographer is as concerned with self-expression as making social statements, being an independent and creative artist.

Street photography represents a discipline of photography that make an artist involved and engaged, though at the same time loose and free in his action, hence subjective. As I have already mentioned in comparison to documentarian or photojournalist, a street photographer is liberated from the guidelines, instruction or any assignments. Therefore, the urban environment becomes perfect for this kind of practice. The genre became a well-respected medium functioning according to its principles of subjective photography “formulated a balance between comment and criticism, description and inscription, where meanings were acknowledged as “fleeting,” as if, like the people in the images, in constant transition themselves” (Bate, 2016, pp. 174-175).

Bridget lives alone in a tent on Gladys Avenue in Skid Row, one of the most violent streets in the neighbourhood. She is pictured here as she takes a break from recycling cans and bottles that she digs from one of the many piles of garbage throughout the area.

Digital era in photography

Generally speaking, digital photography invigorated and extended the ways of space representation and documentation practices, at least due to cameras mobility and camera- phones ubiquity. Plus, digital devices are used to produce a massive number of images, hence they document a much wider range of sites than, for example, analogue cameras (Lee, 2009). Nevertheless, the massive quantity of digitized imaging brings some significant consequences, but it remains unclear and still hard to predict how this huge number of images of the ordinary and mundane will affect our social or cultural life. (Wells, 2015, p. 122).

The quantity of photographs we are facing now is extreme and large-scale, however, we also can observe some personal developments. As photography became a wide-spread practice, it caused an increase in everyday photography. Plus, the lighter and more mobile accessories and devices make the older practices evolve (Lister in Larsen Sandbye, 2012, p. 36).

Despite the quantity of digital imaging, which grows gradually at any moment, people tend to believe in a notion of the 'lack of waste' in the digital age. In this respect, Hand comments that the opportunity of deletion or disability allow people to compile their creative photography skills and this way “digital camera acts as a technology of skill redistribution rather than de-skilling” (Hand, 2016, p. 111).

Mobile phone photography

As it was already told, digital media are all around us and the digital revolution still dictates the terms of the modern being. Digital photography has almost completely pushed out the analogue and has never been so close to us as it is now. Thanks to our mobile phones and the in-built camera feature, digital photography moves to a new level, as the ubiquity of the medium is definitely on its apogee.

Most of the time people have their phones with them, hence the camera function is always available for some unpremeditated and quick shot in keeping with the best traditions of street photography. The medium is so inter-tissued to digital media, “it is becoming something of banality in terms of its corporate, institutional and everyday prevalence” (Hand, 2013, p. 13). Marien mentions camera phones are not just another useful camera tools, but it is basically a camera connected to the Internet, and the way how fast images can be snapped and sent is completely changing the idea of the photograph, transforming it into an instant message (Marien, 2012, p. 191).

The age of the amateur

The new era of wide-spread new technologies, including digital cameras and camera phones, the popularity of social networks and photo communities and groups with absolute user-generated content led to the era named 'Web 2.0 – the Age of the Amateur' (Larsen, Sandbye, 2014, p. 2). If analogue photography was made for the future public, digital photography is made for almost up-to-the-minute users, regardless of the distance between them. Today private snaps of daily life are opposed to traditional press photography, as the access to cameras is easy and cheap for everyone now, and even the concept of 'breaking news' is changing now, implying the amateur mobile-phone recordings (Larsen, Sandbye, 2014, p. 2-4). As it was already discussed, digital photography now, as a result of its collaboration with other evolving technologies, is not just about the quality of the image but more about the ways of distribution, manipulation and different modes of display.

Digital photography ubiquity

These socio-technological processes of total digitization are more than ever relevant to the genre we are discussing. Street photographer's first rule is to be invisible and to blend in the crowd, and the phone with the in-built camera is the device which perfectly suits this job. Moreover, now everyone is a street photographer, both dedicated and unaware. The access to the camera and urban area makes people create in the genre of street photography. Such omnipresence of digital devices and their interconnection with other media is transforming the genre, which has always been exposed to internal (documentary style, photojournalism and Surrealism) and external interferences (consumerism, loss of interest in the genre in favour to other styles, lack of supervision). Now the major challenge to street photography is the most important external influence which is the digital photography ubiquity, expressed in the total vanishing of boundaries between the professional and the amateur.

Invisible observer or artist?

The research I have conducted allowed to come closer to an understanding of the street photography genre, which is, as it was observed a very complex phenomenon in the art world. It has a very rich history and the development of this discipline has never been homogeneous due to a great number of internal and external factors. In addition to its very artist-and-style dependent nature, street photography experiences a new round of evolution thanks to the digital revolution and digital camera ubiquity.

Everyone is technically a photographer now, hence this age of the amateur could not help affect such an absorbing and malleable discipline. Nevertheless, I attempted to study the issue of the location of street photography on the scale between art and documentary, in the context of digital camera omnipresence. To do that I have decided to observe and analyze a great quantity of imagery material on the internet (social-networks and image-sharing sites) and some photo art books (both electronic and paper). The analysis included the determination of regularities, major similarities and differences by three main criteria.

The criteria of the photographer's involvement, according to which an artist can be an invisible observer or an open intruder of the private space. First one is very close to documentarian observance of reality, whilst the second one calls for emotions, hence it is leaning towards art.

The criteria of aesthetic appeal, by which I distinguished two trends: the dark side street photography which stoops to anything (being very close to photojournalism), and includes featuring the lower social strata and even dead people, while the opposite to that is the pure art style causes aesthetic satisfaction with the ideal combination of form and content. And in my honest opinion, the latter one holds the middle ground between art and documentary because can be equally characterized by both realms.

And the third criteria – what are the main motifs on the images. I distinguished the most obvious and numerous tendencies that I could highlight. Geometrical street photography makes this style the most precise and sharp out of all, the most important elements are figures, shapes and lines, whilst the figure of human has secondary importance (although it depends on the photographer, who places the elements as he wants). This sub-style is almost purely artistic because the main focus is the form, however, the human figures may play an important documentary role too. The next type of content is a portrait street photography, within which I observed the smaller tendencies. The common feature is that they all capture the individualities, whether it is a person in natural habitat or candid pictures of passers-by or a staged street style fashion photo of the model. In this case, all of the presented portrait styles range significantly to a different degree between documentary and art, and it mostly depends on the environment of the objects. The next category is juxtapositions, the visual metaphors or visual irony and contrast, which seem to outlived itself thanks to its ‘mainstreamification’ and eventual vulgarization, but anyway it is one of the most obvious trends in modern street photography. It requires to be ready and lucky to catch the perfect contrast moment, but also a photographer has to notice that and this include artistic skills, so this kind is leaning towards art more than to documentary. And the final kind of content is absurd. This implies to weird coincidences, unexpected encounters and presence of some elements where they are not supposed to be present, something that makes the spectator surprisingly ask 'what is going on here?'. I consider this motif as the most 'street photography', due to depicting of the most extraordinary incidents in the most ordinary realms, at the same time it is a documenting on the real-life so all in all it is artistic in terms of narrative and documentary in terms of approach to the objects.

Street photography is not dead

To sum up I have to admit that it is not possible to limit street photography within some strict frameworks because even those tendencies that I examined have their specific nuances and exclusions which make them lean towards either documentary or art depending on the combination of factors such as the artists, environment, techniques, devices etc. None of the described trends is purely artistic or documentarian. The digital age, due to its photo equipment abundance changed the face of modern street photography creating the new tendencies and maintaining the older ones, however, concerns of some critics and theorists about the approaching “death” of street photography are devoid of meaning because in terms of the adaptive nature of the genre it is going to be transforming further.

Andrey Belov-Belikov wrote this thesis for the Master in digital communication and culture 2017.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)