The ecologically thinking eye

Harry Nankin

Ecologically-informed aesthetics: vision alone can imply cognitive separation.

Harry Nankin

The idea of an ecologically-informed aesthetics, the visual dimension of an ecological gaze, may seem at first glance oxymoronic: ecological knowing suggests attachment to a subject but vision alone can imply cognitive separation.

Cultural theorist David Levin reflects the popular social constructivist prejudice that vision is the most reifying, objectifying and hegemonic of the senses, the sense most closely associated with modernity’s will to power (Levin, 1993: 65). Historian Allan Wallach reveals a similar position when he argues the post-enlightenment invention of the vista and in particular the panorama in art are psycho-politically charged; The vista is a “bourgeois vision” akin to Michel Foucault’s panoptical “sovereign gaze” in which we observe the world from upon high literally or imaginatively because we identify our security and power with that of the state metaphorically watching over us (DeLue, 2008: 318). Although the panorama in art did indeed arise in an imperial age it is also true that nearly all people in every culture enjoy high vantage points for observation, safety or refuge and for their own sake regardless of real or vicarious feelings of possession. As philosopher Tim Ingold points out, to philosophical critics of visualism...to see is to reduce the environment to objects that are to be grasped and appropriated as representations in the mind. The irony is that this...[approach]...has its source in the very Cartesian epistemology that they seek to dethrone. What they offer, then is not an account of visual practice, but a critique of modernity dressed up as a critique of the hegemony of vision (Ingold, 2000: 286-287)

The causal link is thus opposite to social constructivist claims: vision is not intrinsically reifying, objectifying or hegemonic. Culture steers it so. In the never-ending nature/nurture debate there is however no doubt hardwiring has some role. Biologist Edward O. Wilson thinks all humans have “biophilia”, a subconscious attraction to living things and species-rich environments (Wilson, 1984; Kellert, 1995). Gordon Orians and Judith Heerwagen present a “savanna hypothesis” explaining the apparent cross-cultural liking for open, gently undulating, lightly wooded landscapes and acacia-like trees with broad canopies and short, branchless trunks as ancient evolutionary adaptations (Orians, 1992; Orians and Heerwagen, 1995: 557; Adevi and Grahn, 2012: 28). Other researchers speculate that the common desire for “neat landscapes” (Williams & Carey, 2012: 259) and for “water, large trees, a focal point, changes in elevation, semi-open space, even ground cover, distant views to the horizon and moderate degrees of complexity” may be instinctive (Orians & Heerwagen, 1995: 560). Outside instinct, personal experiences profoundly influence environmental tastes. Richard Louv has shown how childhood contact with nature is critical to mental and physical well being including the ability to feel comfort in and valuation of the nonhuman world (Louv, 2013). Notwithstanding urban childhoods with little or no experience of the outdoors, other research indicates people tend to “attach to the type of landscape in which they grew up” (Adevi and Grahn, 2011: 47): farm life generates appreciation of agricultural landscapes; lakeside holidays produce a taste for freshwater spaces. The problem is, there is no necessary correlation between instinct or experience and ecological judgement: park-like landscapes may be maintained by overgrazing or a pretty lake may be a dam hiding a drowned forest.

Payment Failed

Land aesthetic

Normative models for an ecologically informed aesthetics have been explored by many commentators; two outstanding examples are Aldo Leopold’s “land aesthetic” in which ecological integrity or “health” is considered the measure of “beauty” (Callicott, 2008:105) and Allen Carlson’s “aesthetic functionalism”, where nested causal relationships define environmental “value” (Bannon, 2011: 417-18). Taking aim at the very notion of such an aesthetics however, philosopher Gordon Graham has argued ecological sensibility renders an aesthetic response “essentially secondary” because it relies on a “truth” revealed through other modes of understanding such as ecological knowledge: we “may wonder at the far-reaching and impressive balance of forces that nature exhibits, but it is scientific and not aesthetic judgement that reveals this to us” (Graham, 2005, 219). Yet this argument fails to acknowledge that just like taste in art, aesthetic responses to nature are unconsciously as well as consciously conditioned by knowledge. It is, for instance, well documented that landscape preferences reflect education and occupation: rural dwellers familiar with the signs of overgrazing see ecologically healthy landscapes as more attractive than do urbanites (Williams and Carey, 2002: 267-8). An ecological gaze is of course more than the expression of internalized knowledge leavened by personal experience: a thinking eye would also be sensitized to ecological embodiment and feelings – the topics of the next two chapters.

Art and the ecologically thinking eye

The symbolic representation of nature – something indicative of fully modern human consciousness – has a ubiquitous presence in art history. Wild animals for instance are the dominant subjects of the oldest surviving parietal art of the Upper Palaeolithic [Fig 2] and Australian indigenous representations of animals invariably reference dreamtime and country. From its beginnings in first century Rome, natural history illustration has reported and/or sought to explain nature’s wonders and workings, whilst ever since its emergence in twelfth century China and fifteenth century Europe the landscape genre has articulated changing aesthetic, spiritual and affectual responses to and ideas about the nonhuman world (Brown, 2014: 9). The emergence of the ‘environmental art’ movement around 1968 (Tufnell, 200:13) reflected a transition from what art theorist Hal Foster called a “vertical” idea of art in which value is determined by style, repetition and method to a “horizontal” approach in which art participates in thematic or cultural discourses, namely environmental ideas (Foster, 1996: 184). Andrew Brown divides the vast, diverse and growing corpus of contemporary ecologically “engaged practice” (Brown, 2014: 9) into a six stream “taxonomy” (Brown, 2014: 15): artists who “re/view” the world by bearing witness to it; those who “re/form” the material environment through creative re- making or re-contextualizing; practitioners whose work is an act of “re/search” into natural phenomena and processes; those who interrogate or “re/use” the culture of consumption and waste; artists who imagine or “re/create” alternative worlds and those who actively “re/act” to the world by intervening to change it (Brown, 2014: 5). Although the materialist “phenomenological or experiential understanding of the site” (Kwon, 2002: 3) articulated by most ecological art practitioners ignores recent critical notions of site as a “social/institutional” space, their work almost always serves what Miwon Kwon calls a “discursive” purpose that interogates theoretical concerns beyond the specificity of any particular site, namely ecological questions (Kwon, 2002: 3). Although all six streams of Brown’s taxonomy point to an ecological gaze with photographic exemplars and ‘landscape’ references, only the first – ‘re/view’ – does so preeminently.

The ecological gaze

The ecological gaze is an art-making concept, a speculative mode of reflection and creation focused in this project on a single medium, photography; but the link between ecology and the photograph extends beyond art. Together, the medium of photography as “art, document, market, and science” (Miller, 1998: 24) suffuses visual culture so completely that “we are still in the process of absorbing its effects” (Thomas et al, 1997: 8). Most importantly, the ‘effects’ of photography’s unparalleled ability to bear witness to or “re/view” the world have contributed to ecological thinking by virtue of doing what only photography can do: record what the naked eye sees and see the erstwhile invisible–from the microscopically small and telescopically distant, the lightning fast and imperceptibly slow, the undetectably faint and blindingly bright–to objects blocked from view and light emanations at wavelengths beyond unaided human perception. Whilst naked eye vision is largely the purview of art, documentary and commercial practice, it is scientific photography–the mainstay of non-naked eye imaging–that has most profoundly informed our vision of nature. As Ann Thomas observes, our contemporary world view owes much to the extraordinary aspects of the universe revealed by photographs of the sun’s corona during an eclipse, the transit of Venus across the face of the sun, and those photographs that capture actions and organisms visible only to the assisted eye–from sequential movements of a galloping horse to “portraits” of bacteria, from the structure of distant galaxies to the mysterious secrets of the composition of matter...(Thomas et al, 1997: 8)

The unphotographable

Many scientific images are of what Jeffrey Fraenkel and Frish Brandt call “the unphotographable” (Fraenkel, 2013); that is, photographs for which the making or content is revelatory, inexplicable or uncanny. Some of these have had momentous impact. Edwin Hubble’s astronomical glass plate of the Andromeda galaxy playfully titled M31 Var! exposed on the night of October 5-6, 1923 at the Mount Wilson observatory in California [Fig 3] proved the Milky Way was but one galaxy among many; that space and time were far more vast than previously imagined. It also suggested that post-Copernican heliocentrism was still naively anthropocentric, for we lived in a universe without centre (Grula, 2008).

A second example was Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray crystallography “Photo 51” [Fig 4]. Made in May 1952, it established the double helix geometry of DNA announced the following year by Francis Crick and James Watson (Maddox, 2012). Perhaps the most famous example–albeit one executed during a scientific enterprise rather than as a scientific investigation in itself–was Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders’ hand-held Hasselblad photograph of the earth taken from moon orbit on 24 December, 1968, the first single natural colour image of the entire planet [Fig 5]. Nicknamed “earthrise”, photographer Galen Rowell described it as “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken” (Life, 2003), a precursor to the global ecological imaginary or “overview effect” enabled by high altitude terrestrial reportage (White, 1998).

The experiments of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century ‘proto-photographers’ that eventually led to the invention of photography were driven principally by a quest to report nature “in terms of landscape” (Batchen, 1999: 69). The idea of landscape was conditioned by conventions of ‘the picturesque’, a mode of seeing and representation described by its chief exponent Reverend William Gilpin as “expressive of that peculiar kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture” (Batchen, 1999: 72). For proponents of the picturesque, the strategy was to find the best viewpoints and locales aided by instruments that helped cohere disordered, three dimensional reality into a pleasing prospect of “simplicity and variety” or a “united whole” (Batchen, 1999: 73). In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries such instruments included the Claude glass, a portable camera obscura (usually with a lens) and after 1801, the camera lucida.

Landscape is vague construct

Like any genre, landscape is a vague construct that in its extensive and eclectic practice overlaps with most other genres and subjects. Dissecting this diversity Estelle Jussim and Elizabeth Lindquist-Cock describe eight themes: artistic genre, God, fact, symbol, pure form, popular culture, concept and politics and propaganda (Jussim and Lindquist-Cock, 1985). Robert Adams classifies the subject qualitatively: every landscape photograph contains the three “verities” of geography, autobiography and metaphor in varying proportion (Adams, 1981: 14). However defined, the critical question is how well photography of landscape measures up to the very distinctive verities of ecological thinking.

The nexus of landscape photography and nature preservation, the birth of photography as environmental ‘politics and propaganda’ (Jussim and Lindquist-Cock, 1985: 137) can be traced to the protection of Yosemite as far back as 1864 (Solnit, 2003), and the establishment, seven years later, of the world’s first ‘national park’, Yellowstone (Rosenblum, 1997: 135; Newhall, 1982: 100). This so-called wilderness tradition is most closely bound up with twentieth century American photographer Ansel Adams’ masterful monochrome craft and sublime vision, which was characterized by the absence of people [Fig 6]. The “long shadow” of his photographic aesthetic, edenic ideals and environmental activism are most obvious in the popularization of the concept, photography and legitimization of the idea of wilderness (Wells, 2011: 136, 137).

Use of colour

Ever since Eliot Porter’s pioneering use of colour in the post war years made it the modus operandi of popular landscape craft (Ward, 2008: 30) the art and polemic of the wilderness style has been sumptuous, popular and global. In Australia among the sub-genre’s most effective exponents was Peter Dombrovskis, whose large-format technique, “exaggerated visual effects”, wide angle views, extreme close ups and low- contrast light (Ennis, 2007: 68) publicized the beauty of endangered Tasmanian environments targeted for conservationist action over nearly two decades. With an Australian Federal election looming in 1983, Dombrovskis’ lyrical Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend, Gordon River, Tasmania 1979 [Fig 7] captioned with “Would you vote for a Party that would destroy this?” (Bonyhady, 1996: 3) was reproduced in newspaper ads across the country. A key element of a conservation campaign against the Federal government that would have permitted the damming of the Gordon River for hydro electricity, the ad tipped sentiment against the incumbent coalition parties and they were swept from power. The development was stopped and the region became a National Park (Ward, 2008: 21). The picture’s singular political efficacy generated a subtext found in all wilderness photographs: vicarious pleasure tinged with anxiety that such ‘perfection’ is easily obliterated. In other words, wilderness images insinuate ‘tragic’ violation by the very omission of that violation.

Wilderness photography

Summarizing its wider cultural impact historian Helen Ennis wrote: Unlike any previous form of landscape photography, wilderness photography clearly enunciated a duty of care, that is, an environmental position based on responsibility for and protection of the natural environment (Ennis, 2007: 68) Yet wilderness photography is also problematic. First, there is the question of the artistic worth of its formulaic technique and nostalgic Edenism. Second, there is its uncertain ecological credibility; by excluding human presence wilderness can appear misanthropic and paradoxically, ecologically false and idealizing (Franklin: 2006; Stephenson, 2004). Third, wilderness is accused of being “green pornography” or “eco-porn” generating desire for touristic or vicarious consumption by objectifying its subject in the same way that sexual pornography incites lust (Drysdale, 1995). Martin Walch extends this analogy by dividing profit-driven “hard-core exploitation” imagery used to market unrelated products from the “soft-core objectification” of “nature-kitsch” designed to “incite desire for natural environments”. He excludes artists like Dombrovskis from the accusation but exceptions do not mollify the larger problems of idealising falsity and commercial objectification (Walch, 2004: 3-6). Paradoxically, it is partly these very faults that render wilderness an instance par excellance of Kate Soper’s “provocatively contradictory notion” of “avant-garde nostalgia”, which is a movement of thought that...could here make a contribution by reflecting on past experience in ways that highlight what is preempted by contemporary forms of consumption, and thereby stimulate desire for a future that will be at once less environmentally destructive and more sensually gratifying (Soper, 2011: 23-24).

By cataloguing the look and lives of nonhuman nature, the genre most closely aligned with both science and the wilderness tradition – natural history photography – aids ecological thinking by reporting animals in their environment. Wildlife photographers from Patricio Robles Gil, Xi Zhinong, Art Wolfe and Frans Lanting [Fig 8] to David Doubilet, Mitsuaki Iwago and Michael Nichols employ image and word to celebrate their nonhuman quarries individual lives and habitats but also indicate their fragility. Sabastiao Salgado foregrounds this subtext by engaging in an “ecological pedagogy” in which by approaching wildlife with the same moral sense he previously documented the poor (Nair, 2011: 116), he questions “the premises of humanism, whereby the human is exalted over the nonhuman” (Nair, 2011: 22-23). In other words, the evident fragility of wild creatures insinuates their vulnerability and their connectedness to us [Fig 9]. Although natural history photography can tend to anthropomorphism and, like wilderness, to ecological idealization and soft-core objectification, it is also at least as effective as the wilderness tradition at indicating what in the nonhuman world is being ‘preempted by contemporary forms of consumption’ as the wilderness tradition.

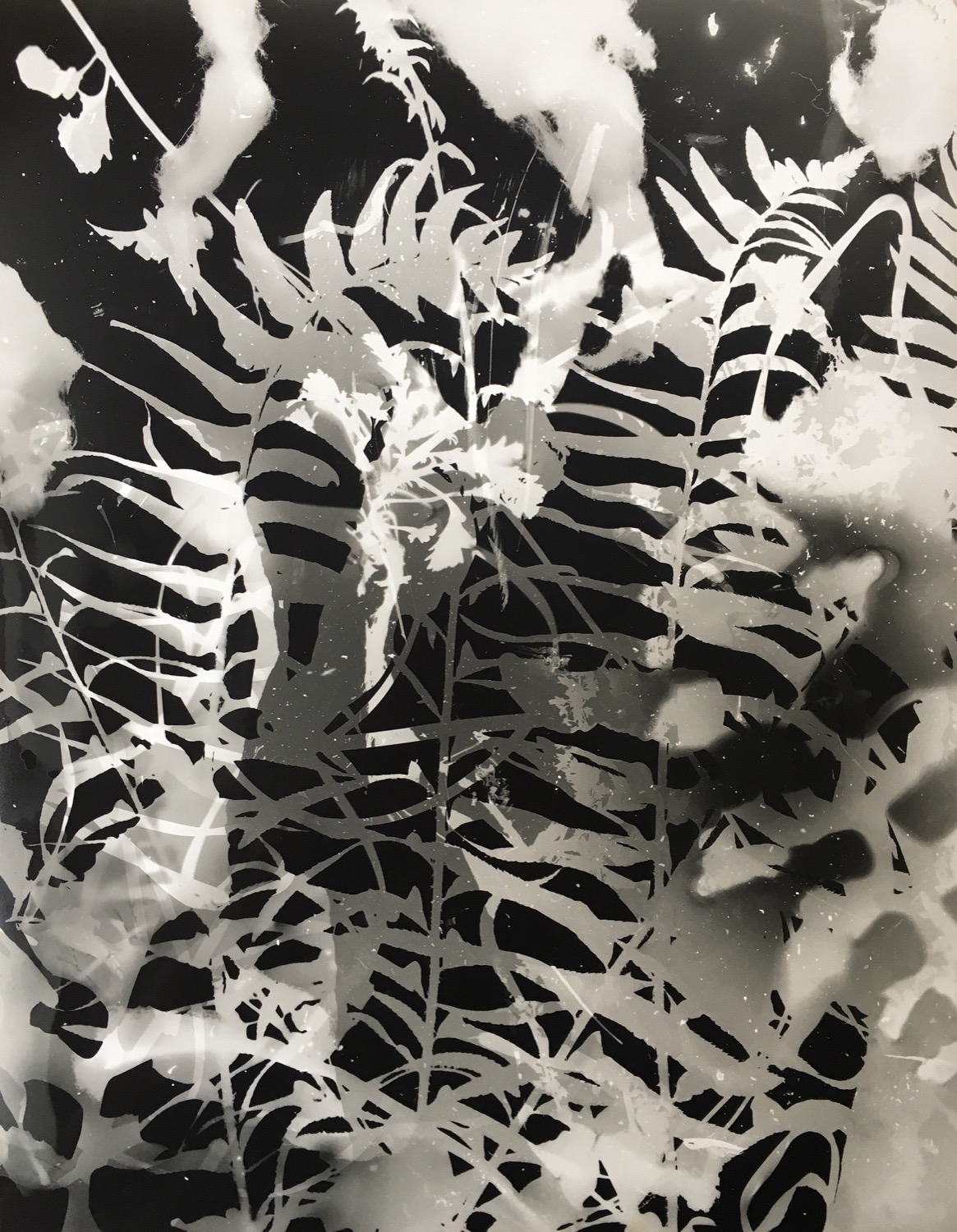

The imagery of Gathering Shadows reflects and reflects upon the emerging global phenomenon of environmental psychic distress that Glenn Albrecht terms solastalgia (Albrecht et al, 2007). It does this by recognising that an oblique index of shadows rather than direct wilderness or natural history reportage will do what science excels at – reveal the hitherto invisible – whilst impressing upon us the disturbing sensation of ‘avant-garde nolstalgia’ for worlds not yet lost (chapter 2). And, the work acknowledges that reportage of the purportedly unsullied nonhuman world is not only ecologically informative but potentially unsettling, that is, generative of an ‘avant-garde nostalgia’ at once sentimental and subversive, that has driven the turn towards wild creatures–principally invertebrates – inferring the tragedy of landscape (chapter 3) at Lake Tyrrell (chapter 4) and Mount Buffalo (chapter 5).

This essay is a part of the thesis of Harry Nankin, Gathering Shadows: landscape, photography and the ecological gaze, written in 2014 at the RMIT University Melbourne, for the the degree of doctor of Philosophy

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)