The Photograph as Metaphor

Minor White

Does a photograph show the reality? Or does it show the emotions the photographer wants to show?

Artdoc

Does a photograph show reality? Or does it show the emotions the photographer intends to show? An investigation into the photograph as a metaphor and the psychology of perception, with the theory of equivalence of Minor White as a guide. According to White, the Equivalence is ‘the backbone of photography as a medium of expression-creation.’

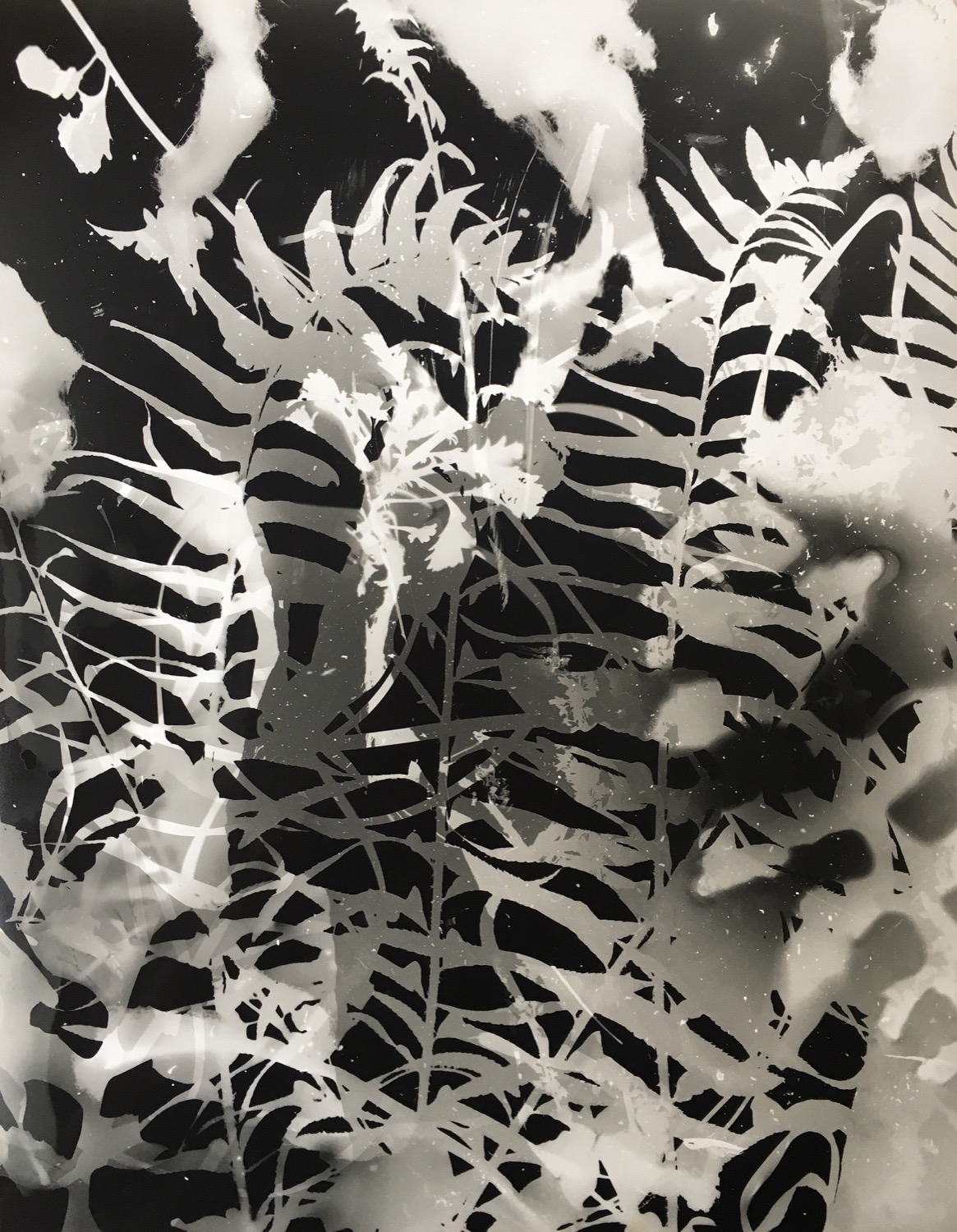

Looking at the photograph by Minor White, Portland, Oregon, 1964, I observed that harmonious lines, luminous leaves that seem to reflect light, surfaces with deep blacks and lines crossing each other. The proportions of the image and the subtle details strengthen the calm that radiates from the photograph. The fact that the photograph is made in subdued light, and that the photographer has consciously made use of it, gives me as a viewer a certain form of deep emotion. There isn’t much to see in the photograph. There is no event that I can analyze, no story, no anecdote. There is only the photographer's attention to a small piece of almost insignificant reality, sharply etched leaves, worn-out wooden fence, and rich contrasts.

But because the photograph is abstract and at the same time, extremely concrete, it is an excellent example of the most elementary form of visual language. What is this photograph about? Does it deal with structures, harmonious lines with light and shadow? Or with something else, something that is alluded to, but remains invisible?

Psychology of perception

The philosophy of photography struggles with one great problem; a photograph is supposed to be a representation of reality. While painters have the opportunity to make their interpretation visible utilizing a particular style or through a special technique, they can paint their dreams and fantasies directly onto the canvas. In contrast, a photographer must start from the visible, even when he arranges the scene himself. This concept makes him a servant to the visible and gives photography a mechanical and impersonal aspect. But precisely this fact that the visible reality is the starting point enables the photographer to develop something very primordial: perception itself, and connected to this is the psychology of perception.

The photographer’s perception has two extremes: the world outside him, which is the visible, and on the other hand, the world inside him, his consciousness. The outside world is an infinite field of possibilities from which he can select. The photographer, who is shaped by his past, his upbringing, and his social and cultural situation, makes the choice of subject and the form in which the shot is taken and presented. How he looks at the world is charged with a certain view and attitude and will determine what and how he photographs.

Art historian E. H. Gombrich, one of the first to study art from a psychological perspective, speaks of 'mental sets.' Every artist observes from within a mental scene, which among other things, is determined by the expectations with which he perceives reality. Since the philosopher Kant, we know that any perception whatsoever can only occur via categories inherent to the mind. When viewing and interpreting a photograph, the above will have to be taken into account.

'Art being a thing of the mind, it follows that any scientific study of art will be psychology.’

Max J. Friedlander/Von Kunst und Kennerschaft

Language of the image

What does the photo of Minor White inform me about? If I want to answer this question, I will have to ask myself what the relationship is between the image and layers, which remain concealed. In terms of the science of semiology, brought to photography by Roland Barthes, we have to ask the relation between the signifier and the signified, the sign and what it means. Photography speaks a different language from the verbal language, a language that is primordial, but by no means less complex: the language of the image. Just as words refer to meanings, the image-elements of a photograph also refer to meanings.

It would be a misconception and a simplification to assume that a photograph only refers to the visible reality, which it renders two-dimensionally. If I want to understand White’s photograph, I must learn to read its language. Why does the photograph make me think of peace and harmony, but at the same time, the shadows of life? The photo appears to be deep attention to the natural world, to a bond with the earth, harmony, and dark memories of a past. The photograph bridges the gap between matter and mind, which brings me beyond its own depiction. To understand this, we have to take the road back, from the external, visible world to the invisible, internal world: the mind.

Metaphor

Actually, a photograph is a metaphor, a figurative expression that is based on a comparison. The photographic representation of reality is a metaphorical image of another reality, which remains visually absent. The photograph speaks in metaphors, its story consisting of images without words, fixed images, moments, and places, visual abstractions in space and time. Besides, what they represent are ideas, feelings, emotions, views, opinions, and commentaries. Photography doesn't depict reality, but always refers to a view and concept of reality. It shows how the world is experienced, how the reality is filtered and experienced by the photographer's consciousness.

This is why photographs are metaphors. Technically viewed, photos literary are prints of the visible, but merely as images, as visual words. The metaphor connects reality, as it appears to us through the senses, with the reality that we know mentally, both intellectually and emotionally, as an internal experience. The photograph as a metaphor is the visualization of this connection, and as such, it is a presence and absence at the same time.

Dichotomy

Take another photograph, one by Sebastião Salgado, Korem Camp, Ethiopia, 1984. Salgado was not considered as an artist in the time he took the picture, but as a photojournalist who used to photograph suffering, poverty, illness, and death all over the world. The photograph poses a problem for me. Can I, as realistic as the image is, see it as a metaphor, and thereby deny the harsh reality of that moment? Here we hit upon a basic dichotomy that runs through all photography: photography as art and photography as a document. Art photography is considered a form of expression of the photographer, whereas documentary photography is, or aims to be, a realistic portrayal of reality.

The critic Allan Sekula takes this dichotomy as a starting point when he compares two photographs, one by Lewis Hine, depicting immigrants leaving a ship, and one by Stieglitz, ‘The Steerage.’ According to Sekula, Stieglitz's photograph functions as a metaphor, while Hine's documentary photograph is a metonymy. That is, the photograph is part of a whole to which it refers. For Sekula, the term 'metaphor' has a quite negative meaning because it alludes to a bourgeois aestheticism, of which Stieglitz is an example. According to Sekula, documentary photography is not metaphorical. This will indeed be the case if we give a limited meaning to the metaphor. The photography by Sebastião Salgado not only connects the image of the refugees with his consciousness and with his concerns about the human condition but also refers to human life in general. By our act of empathy, we can connect ourselves to the image. The images became an archetype for human suffering.

Payment Failed

Psychology of perception

We need a study of the psychology of perception, the photographer's, as well as that of the viewer. The psychological processes in the production and in the reception of photography deserve more attention because visual language uses an image-vocabulary of which the elements are often deeply hidden in the subconscious. The psychological approach doesn’t necessarily entail a rejection of semiology, but can actually make use of it. After all, semiology has made valuable distinctions, such as those between denotation and connotation, between signifier and signified.

The film theorist Christian Metz connected psychoanalysis with semiotics in the semiotics of film. He compared a film to the dream and searched for the code of that dream. His comparison is mainly based on the scenario of narrative films and is therefore inapplicable to all photography. Photography could better be compared to the act of recollection, because the images of our memory, just like photographs, are often still images.

Psycho-analytical

A photographer, who uses the metaphor as a tool, makes ‘memory images’ of his experience. For him, the decisive factor is not the moment, but his reaction to and expression of that moment. Does this also count for the photojournalist? Here we have to address the problem of the analysis of documentary photography in psychological or psychoanalytical terms. A critic of the Marxist school, like Sekula, would object that this is a flight into aesthetic domains. His accusation would be true if the social context were left out of consideration. By nature, a photojournalist isn’t primarily concerned with his subconsciousness, memories, or his emotions, but this doesn't make how he looks at his subjects less determined by psychological factors. A seasoned photographer will be aware of his emotional and intellectual reactions to events he photographs and will give an account of this in his photographs. The Barthesian definition of the essence of photography as ’that-has-been’ could be read as an implicit explanation of photography as recollection because a recollection is always of something that has been. A dream is merely dreamed. Photography can be defined as a visual account of a personal or collective memory, a fixed moment of a ’state of mind,' the print of an internal image.

Are there general laws in the perception of images that connect the photographer to the viewer, ensuring that I can read and understand the photograph in accordance with the photographer's intentions? Are there rules connecting all photography, or must we learn to read every photographic style to understand them? Does a dark photograph always mean fear and melancholy? How do I know that I interpret the connotative processes correctly, and how do they influence my perception of a photograph psychologically?

Equivalence

When we describe a photograph as a vehicle of a recollection, both individual and collective, it means that we need to recognize the image as a memory. The inherent aspect of recollection inside the image is a prerequisite for the spectator to read a photograph as more than a copy of the reality.

Recognition and recollection have deep roots in our subconscious, which is why they determine our perception of the reality vaguely or clearly. This is where Minor White referred to as ’Equivalence,' a term he took from his predecessor Stieglitz. According to White, the Equivalence connects the photograph to the psyche of the viewer by means of recognition.

In his article, Equivalence: The Perennial Trend. (1963), he claimed that Equivalence is ‘the backbone of the photography as a medium of expression-creation.’ The photo can function as an equivalent if the individual viewer realizes that what he sees on the picture corresponds to something within himself.

White makes the connection between the Equivalent and the metaphor in the following quote: “When any photograph functions for a given person as an Equivalent. We can say that at that moment and for that person, the photograph acts as a symbol or plays the role of a metaphor for something that is beyond the subject photographed.”

Thus, the photograph as metaphor appears to be a vehicle that connects the viewer with his recollection, his memory, and briefly his own experience of the reality. The photograph cannot be described as a record of the bare reality but as a reminder of our memory.

Philosophically seen, photography can be taken as a living proof that ’reality' is not something we can perceive directly. Photography, as either art or documentary, demonstrates that every point of view provides a different image, thereby refuting every form of naive realism. The magical fascination we experience when looking at a photograph, even of well know places, is proof of the incomprehensibility of reality itself. A photograph is never mere representation, but foremost an expression. Photography is not realistic, nor is it the reality.

Equivalence: The Perennial Trend, Minor White, PSA Journal, Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 17-21, 1963

http://www.jnevins.com/whitereading.htm

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)