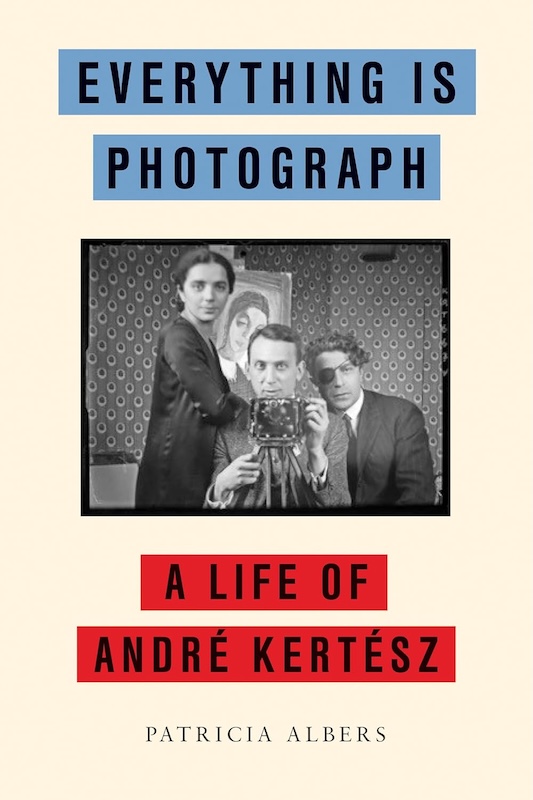

EVERYTHING IS PHOTOGRAPH: A Life of André Kertész

EVERYTHING IS PHOTOGRAPH immerses readers in the heyday of a now-lost version of photography and the life of a consummate interpreter of the world around him. Freshly seen, formally vigorous, emotionally rich, and aesthetically charged, Kertész’s images speak of the medium as a tool for human connection, inquiry about the world, self-narration, and self-invention, even as they project its mysteries. In the words of the legendary curator Jean-Claude Lemagny, “We begin to suspect that to grasp Kertész’s ungraspable secret would be to grasp the very secret of photography.” I hope to stay in contact with you about possibilities for it.

Born in Budapest in 1894, André Kertész soared to star status in Jazz Age Paris, tumbled into poverty and obscurity in wartime New York, slogged through 14 years shooting for House & Garden, then improbably reemerged into the spotlight with a 1964 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. By the time of his death in 1985, he had exhibited around the world, taken more than 100,000 images, and steered the medium in new and vital directions: He was the first major photographer to embrace the Leica, the camera now mythically linked to street photography, and he pioneered subjective photojournalism, publishing what is arguably the world’s first great photo essay.

From the day he first picked up a camera at age eighteen, Kertész brimmed with unorthodox ideas about what photography could do. He conceived of the portrait in absence (a still life selected and arranged to express the animating spirit of the objects’ owner). Working for the French avant-garde weekly Vu and for Germany’s innovative mass media magazines of the 1920s, he pioneered subjective photojournalism and explored the optical distortions caused by water, headlights, and funhouse mirrors. As an octogenarian, he turned to the Polaroid to take still lifes as a way of processing his grief over the loss of his wife. In a century when photography revolved around war, social upheaval, outsized personalities, and fashion, this self-declared amateur kept his gaze on what mattered to him.

Earlier writers about Kertész’s life and work have often focused on his Hungarian, French, or American periods. Some have fallen prey to his insistence that the photographs alone tell the definitive story of his life and work. The diaristic quality of Kertész’s images, along with photography’s factuality, lend weight to that idea. Yet they are highly selected: what he photographed, which negatives he printed, which prints survive. What’s more, they are simultaneously transcriptions of the real and artificial constructs: they both reveal and conceal.

Drawing on dozens of interviews, previous scholarship, and deep archival research, and interrogating the images themselves, Albers retrieves aspects of Kertész’s life that he and his pictures gloss over, among them the ordeals of trench warfare, the impact of the Holocaust, and the tale of his tangled romances. She takes Kertész and his cameras from the Eastern front in World War I to the Paris of Piet Mondrian, Colette, Alexander Calder, and a lively Central European diaspora. From Condé Nast’s postwar media empire to the “photo boom” of the 1970s. She revisits Kertész’s relationships with other photographers, among them his frenemy Brassaï and protégé and “little child” Robert Capa. She breathes life into a gentle, generous, and unassuming man endowed with Old-World charm but also sputtering with grievance and rage and inclined to indulge in deception.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)