Two border posts along a ditch

Jasper Bastian

About the border between Lithuania and Belarus.

Artdoc

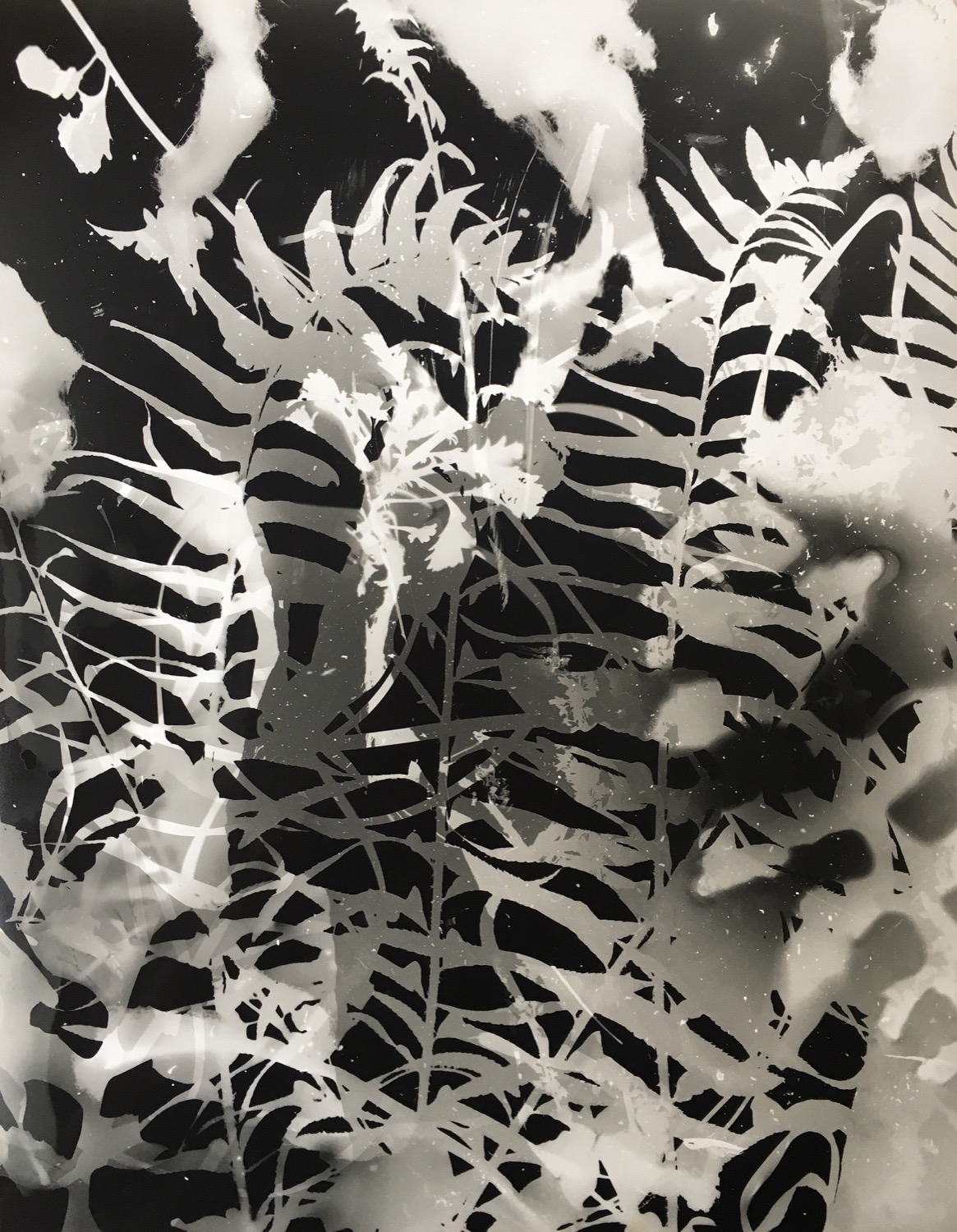

The border between Lithuania and Belarus was once an insignificant line on the map, until the Soviet Union fell apart and Lithuania became a part of Europe. Now the border area represents the dividing line between two cultures. Over the course of three months, photographer Jasper Bastian made three trips to this border area, where he made his project with the title A road not taken, as his graduation project for the University of Dortmund. His images have subdued colours, partly due to the atmosphere of winter, but also because Bastian deliberately kept the saturation of his analogue shots low. "Winter is the hardest time for the people there and I wanted to show that. The isolation and loneliness are most visible in winter."

Symbolic of the whole series is a picture taken in Pašalčis. The picture shows a ditch with a brand-new border post on both sides, one on the Lithuanian side and one on the Belarusian side. The photo tells a small story of a border, but it says a lot more about the large borders that run between two different cultures and economies. "The situation was surreal, because within a metre you could walk from Europe to Belarus. For me, the photo has a lot of meaning in the context of the broad discussion of migrants and the European borders."

Payment Failed

How did Bastian choose this border area as his subject? "Before this project, I made a series in Kosovo called Across the River, about Mitrovica, a city on the border between Kosovo and Serbia on both sides of the river. This sparked my interest in the problems of border areas. Here people live separated by a border and have such a strong hatred against each other. My project was also about conflicts between national identities. After this project, I was looking for a new story with different aspects of borders and nationalities. This is how I came across the border between Lithuania and Belarus. The border between these countries has changed four times in the last century. In the thirties the same people lived in Poland, then it became Germany, then it became the Soviet Union and then Belarus and Lithuania. Some residents were given different passports four times without ever leaving their homes. There were also areas where people lived together for a hundred years without worrying about their nationality and suddenly ended up in a completely different world".

The biggest change is that the border between Lithuania and Belarus has now also become the border between the democratic and free Europe and the still dictatorial Belarus. "There are people who live on one side of the village in Europe and on the other side, behind a big fence, the same villagers live in a communist system. Entire families are separated because of this. I met someone whose sister lived on the other side of the border. Or even worse, I met a woman whose husband lived on the other side of the border. The man got a job on the Belarusian side of the border and went to live there temporarily. She continued to live in her mother's house and he travelled up and down to his wife, but since they can no longer cross the European border, they live completely separated. Now they haven't seen each other for seven years, while it's a distance of only ten minutes by car. It's very bizarre."

Lonely person

Stanislav lives with his dog in the border village of Norviliškės, the last house before the border on the Lithuanian side. In the picture, we see a gloomy looking man sitting on a wooden bed in a shabby interior. Stanislav's aunt lives 400 meters away in Belarus. To visit her in the village of Pizkuny he has to drive 150 km. The border in the village is open three times a year, but to cross the border Stanislav needs a visa, which is too expensive for him. "I have visited him several times. He lives very close to the European border. His village and that of his aunt’s were originally one village, but is now separated into two parts. He is the loneliest person I have ever met. Near his house, the border control with dogs runs up and down. Sometimes he is allowed to talk to his sister on the other side of the fence. He shouts loudly so that residents of Pizkuny hear him on the other side of the border. They call his aunt so he can talk to her."

No future

Jasper Bastian photographed on both sides of the border. One would expect that the economic situation on the European side would be much better, but that turned out not to be the case. "During my visits, the Lithuanian side wasn’t much wealthier than the Belarusian side. There was an economic malaise in both areas. People live in small villages far from the big city and its economic progress. Most people I met were retired or unemployed. They used to work in the Soviet kolkhoz and when the economic system changed, there was no work for them anymore. They couldn't get used to the European way of working and still had nostalgic memories of the Russian system. There was more security and safety for them in those times. All the young people from this region disappeared to the capital Vilnius. I've only ever met two young people in this completely isolated area."

In one picture you see a ladder against a tree, most likely someone planning to saw off and collect branches to heat their house. However, you could also take the picture metaphorically. The stairs lead nowhere, no future at the end of the steps. "Most people don't have a gas connection. They depend on nature. There are no supermarkets to buy food or other things. There's just going to be a driving car-shop."

Analogue

Why does a young photographer still work analogue in this digital time? Bastian: "I've been working with a Mamiya 7, an analogue viewfinder camera with one or two lenses, for the last seven years. I like it when I don't immediately see the images I’ve shot. This way I don't have to look at a display all the time, which would be very distracting when trying to talk to people I’m photographing. This allows me to concentrate better on the moment. I can only capture ten shots per film, which makes me very aware of every shot I take. It slows me down. When I approach people who are not used to photography, my analogue equipment turns out to be less threatening. I also like the special quality of film." For Jasper Bastian, photography plays a role in his vision of how we communicate around the world. I only want to deal with subjects that I consider important. I take a lot of time to explore my themes. I think the addition of text to photographs is key, as not all information can be portrayed through one image."

Jasper Bastian, b. 1989, is a German-American photographer. He holds a BA in photography from the 'University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Dortmund' and studied photojournalism at the ‘Danish School of Media and Journalism’. Applying diverse visual strategies, Bastian’s photography addresses modern concepts of territory and the intricate relationship between identity and place. He is Based in Dortmund, Germany.

Bastian was a finalist for the 'Leica Oskar Barnack Newcomer Award' (2014). He was also selected as one of the winners of the '30 under 30' competition by Magnum Photos (2015) and nominated for the 'Unseen Dummy Award' (2017). His photographs have been published in The New Yorker, Financial Times Weekend Magazine, The Washington Post, Die Zeit, among others.

@jasperbastian www.jasperbastian.com

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)