Blueprints, Botanicals, and the Contemporary Cyanotype

This essay traces the cyanotype’s shift from scientific tool to contemporary photographic language.

Artdoc

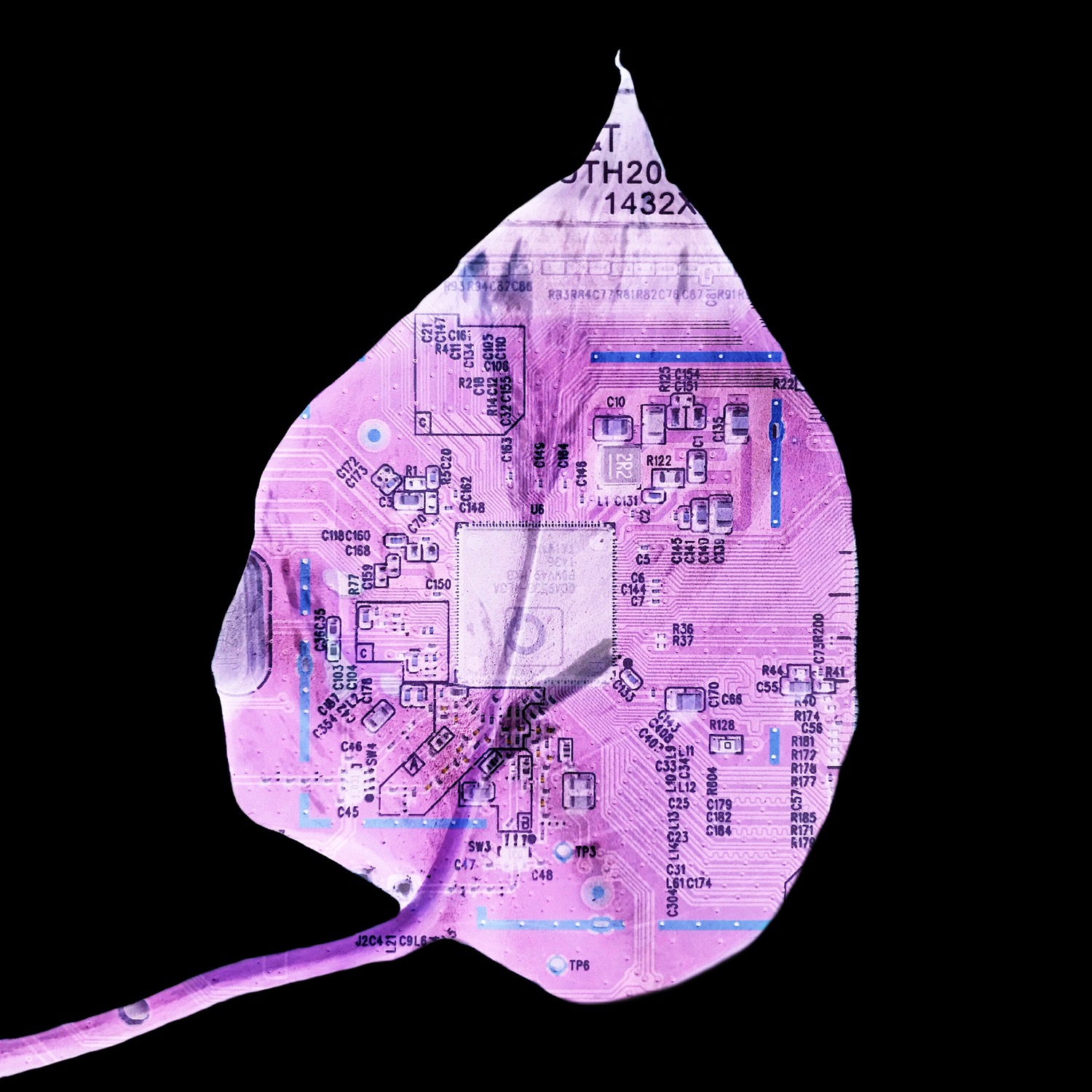

Cyanotype’s journey from a nineteenth-century scientific tool to a contemporary photographic language reveals a profound shift in how images are created and understood. Once valued for precision and reproducibility, the process has been reclaimed as a medium of slowness, material sensitivity, and attentiveness to natural cycles. This transformation reflects a broader movement away from documentation toward dialogue, in which photographs emerge through collaboration with light, time, and organic matter rather than through control or mastery. In this context, cyanotype’s contemporary significance lies not in nostalgia, but in its ability to hold uncertainty, care, and a renewed ethics of looking—inviting images to function less as records and more as sites of relationship.

Payment Failed

Cyanotype entered photographic history not as an expressive medium, but as a tool of clarity and control. Developed in the mid-nineteenth century, it served science, engineering, and botany—fields concerned with classification, measurement, and reproducibility. The distinctive Prussian blue surface was valued not for atmosphere or ambiguity, but for its reliability. It rendered information visible, transferable, and fixed. In its earliest uses, cyanotype helped to map the world.

That this process has become central to contemporary photographic language centred on fragility, ecology, and memory signifies a profound cultural shift. Among artists working today with alternative processes, cyanotype has been reclaimed as a method of slow observation and experimentation rather than description—one that emphasises material presence and the boundaries of human perception. In a growing field of contemporary practice, cyanotype has developed from a technical blueprint to a botanical method, from mere documentation to engaging in a dialogue with the forces of nature.

This shift is not merely aesthetic. It signifies a wider change within photographic culture: moving from mastery to attentiveness, from certainty to relationship. The works of Gemma Pepper, Sarah Rafferty, Xenia Chetrar, and Melanie Schoeniger present distinct yet interconnected views on how cyanotype is being utilised to reimagine our engagement with nature, time, and image-making itself.

The Modern Cyanotype Process

In its contemporary use, cyanotype is seldom created with a camera. Instead, it is a cameraless photographic process that depends on direct contact, exposure, and the physical placement of materials onto sensitised paper. Plants, feathers, printed negatives, and found objects may be arranged by hand, allowing light to interact with these forms through exposure. In many contemporary practices, this involves placing a transparent printed negative sheet directly onto the sensitised paper, so that light passing through the transparency activates the chemical compounds beneath, establishing a direct, material relationship between image, surface, and process.

This method extends beyond traditional sunlight exposure by incorporating ultraviolet (UV) light. By modifying the light source, artists can control the intensity and effects of exposure more precisely. UV light, often employed for more subtle and detailed results, further influences the relationship between the material and the image, heightening contrasts or softening the delicate blue tones typical of cyanotype. The process involves not only the chemical interaction of light with paper but also a meticulous choreography of light, time, and the objects placed on the paper, each producing unique variations. The result is an image that doesn’t just capture the scene but evolves over time, with each exposure shaping the photograph as a collaboration between light, object, and surface. This approach to working challenges traditional photography’s dependence on a lens and highlights proximity, texture, and the flow of time. The cyanotype process, with its cameraless and experimental nature, rejects the mastery of optics, offering a slower, more embodied way of seeing.

Relearning How to Look

If cyanotype once served to stabilise the world, its contemporary use often begins by unsettling habitual ways of seeing. Sarah Rafferty’s series Looking Up emerges from a literal and conceptual shift in attention. During a residency, she found herself disengaged, looking downward and registering little beyond a blur of leaves. A visit to an arboretum disrupted that orientation. Forced to look upward by towering evergreens, she encountered a new visual rhythm—patterns of light, scale, and structure that had previously gone unnoticed.

This change in perspective became a quiet methodology. Rafferty’s work does not impose narrative but asks viewers to consider how perception itself is shaped by posture, habit, and pace. Her images are less about trees as subjects than about the act of noticing—about what becomes visible when the body and gaze are reoriented.

A similar attentiveness underpins Gemma Pepper’s The Voice of Nature, though her work ventures further into imaginative realms. A dancing horsetail, a melancholy sunflower, a solitary black cumin: Pepper’s cyanotypes depict plants as expressive beings, not literally, but as carriers of resonance and identification. While recognising that plants do not experience emotion as humans do, her work explores how their forms and behaviours can evoke states that reflect our own.

Pepper’s cyanotypes defy precise description. Rich blue areas soften edges and blur details, prioritising gesture and suggestion over clear identification. Through meticulous arrangement and prolonged exposure, sometimes lasting up to an hour, time becomes embedded within the image. The outcome is not a botanical illustration but a visual reflection on shared existence, reminding viewers of their entanglement with the natural world they often instrumentalise.

Memory, Material, and the Unpredictable

Where Pepper and Rafferty work through attention and perspective, Xenia Chetrar approaches cyanotype and analogue processes as tools for navigating memory and identity. Her Dreamscapes occupy a space between documentation and reverie, using film photography, double exposure, and cyanotype to construct images that feel suspended between past and present.

Chetrar’s embrace of analogue unpredictability is central to her practice. Film, with its tactile presence and susceptibility to chance, allows her to work with uncertainty rather than against it. Cyanotype, in this context, becomes a collaborator rather than a technique—its chemical responsiveness echoing the fragility of memory itself. Light leaks, layered exposures, and tonal shifts do not detract from meaning but generate it, producing images that resist resolution. Her portraits of women, often enveloped in shadow and light, do not assert identity so much as suggest it. They exist as traces rather than declarations, shaped by the cyanotype process, which is intertwined with her intention. In this way, Chetrar’s work aligns cyanotype with a broader contemporary impulse: to allow photographs to remain open, provisional, and emotionally porous.

Process as Ethics

Melanie Schoeniger’s work highlights the ethical implications of alternative processes. Her cyanotypes explore the symbolism of the peony—its fleeting beauty, cultural mythology, and connection to cycles of growth and decay. For Schoeniger, cyanotype is more than an aesthetic choice; it is an ecological and philosophical one.

Working with toned cyanotypes that avoid plastic and gelatin, she integrates natural materials directly into the image-making process. Unpredictability is embraced as a parallel to life’s unfolding patterns, reinforcing the idea that flourishing is not a fixed state but an ongoing journey. Infrared imagery, UV light, and chiaroscuro effects reference both Renaissance painting and expanded perception, gesturing toward what lies beyond human sensory limits.

Her work does not position nature as a resource or backdrop, but as collaborator and teacher. In doing so, it reframes cyanotype as a medium capable of holding ecological responsibility—not through didactic messaging, but through material choice and processual care.

Time Made Visible

Across these practices, cyanotype serves as a temporal medium. Unlike digital photography’s instantaneity, it requires duration: exposure to sunlight, waiting, and accepting variables beyond control. This temporal aspect aligns with themes many contemporary photographers are exploring—impermanence, transition, and the slow rhythms of natural systems.

Double exposures left in the sun, film subjected to chance, botanicals gathered over time rather than chosen for perfection: these slow actions oppose the acceleration of visual culture. They ask what it means to stay with a process long enough for change to register. In this way, cyanotype becomes not just a look, but a rhythm—a method of working that reflects the cycles it depicts.

This attention to time also complicates authorship. When outcomes are shaped by weather, chemistry, and organic decay, the photographer relinquishes complete control. The image becomes a record of collaboration between human intention and non-human agency, unsettling traditional hierarchies of maker and subject.

Beyond Projection

A recurring tension in contemporary nature-based photography is the risk of projection, whereby human emotion or meaning is attributed where none exists. The artists gathered here navigate this tension with care. Gemma Pepper acknowledges the physiological, rather than emotional, responses of plants even as she explores their expressive potential. Sarah Rafferty frames her work as a shift in human attention rather than an interpretation of arboreal intent. Xenia Chetrar’s portraits hover between memory and abstraction without claiming psychological certainty. Melanie Schoeniger foregrounds process and interconnectedness over symbolism.

Together, these approaches suggest a way forward for photographic engagement with nature that neither romanticises nor objectifies. Cyanotype, with its historical roots in science and classification, becomes a particularly fitting medium for this approach. Its contemporary use does not reject its past but repositions it, transforming a tool of description into a space of reflection.

A Medium Reconsidered

The resurgence of cyanotype in contemporary photography is not merely a nostalgic return to an outdated technique. It reflects a re-evaluation of what photographic practice can offer in a time characterised by ecological uncertainty, technological saturation, and a renewed craving for meaning rooted in material reality.

By shifting from a blueprint to a botanical approach, cyanotype has abandoned its role as a neutral recorder and taken on a more complex identity—as a medium of care, slowness, and ethical engagement. In the hands of artists like Pepper, Rafferty, Chetrar, and Schoeniger, it becomes a way of staying with what is fragile, overlooked, or in transition.

These works do not provide answers so much as conditions for attention. They ask viewers to look again, to look differently, and perhaps to recognise that the act of looking itself carries responsibility. In this sense, cyanotype’s contemporary relevance lies not in its colour or chemistry, but in its capacity to hold space—for uncertainty, for relationship, and for a renewed understanding of how images might help us live more attentively within the world they depict.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)