Europe as a natural park

Claudius Schulze

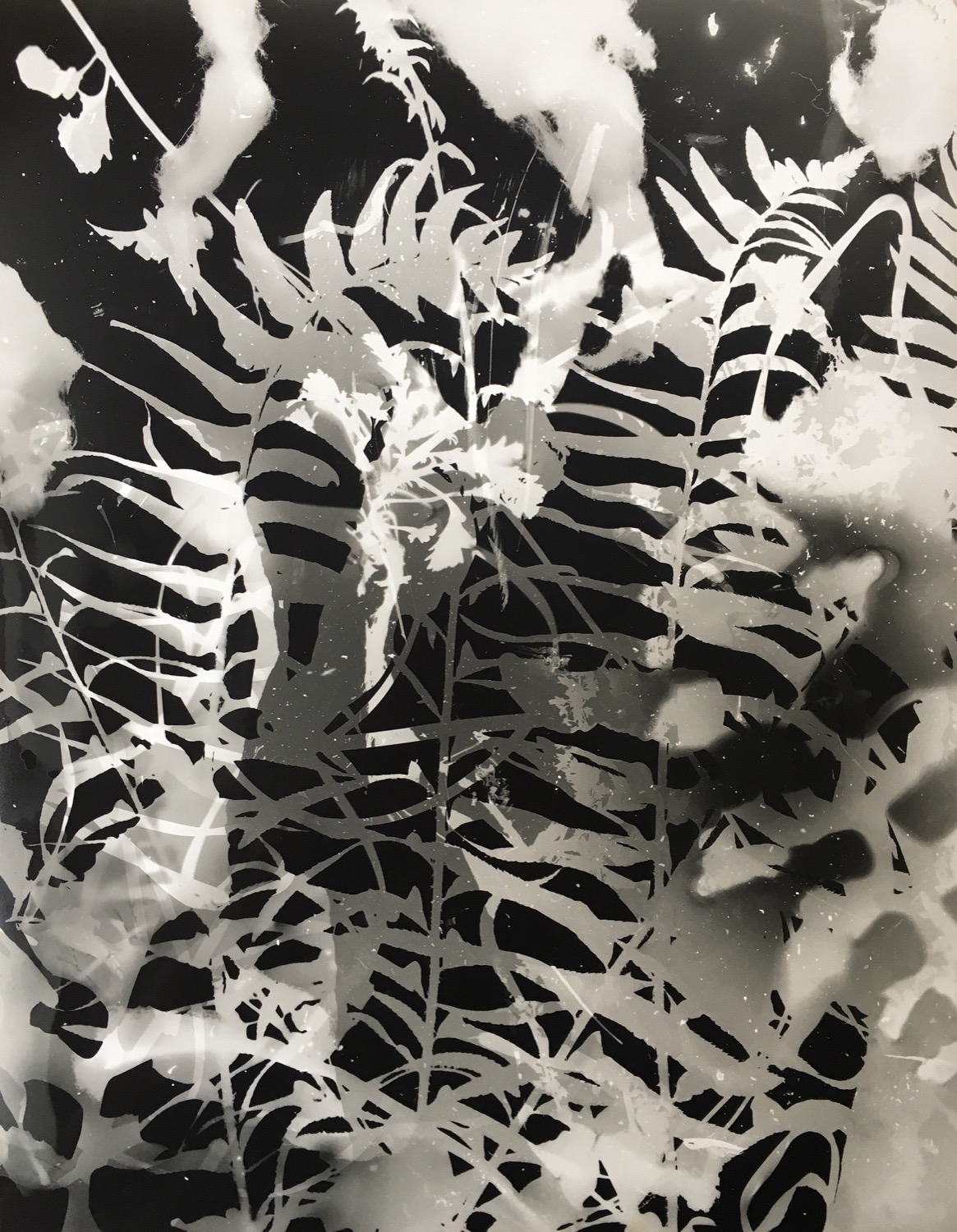

In State of Nature, Claudius Schulze approached nature as a human construction.

Artdoc

Geologists call the current geological era the Anthropocene, the epoch in which the climate is strongly determined by human influence. As a result, the experience of nature has also changed. What we once considered picturesque now has a human layer. The beauty of nature is no longer equivalent to that of Ansel Adams' romantic photography. In his State of Nature project, Claudius Schulze approached nature as an utterly human construction. He aesthetically photographed landscapes that show constructions made by civil engineers to prevent natural disasters. “These concrete structures are an inseparable part of our nature. The European landscape is no longer wild nature, but a large landscaped garden; a park in which we must feel safe.”

Claudius Schulze travelled for five years through Europe where he started his photographic search for iconic plates of nature, in which human input is visible. “The motivation to do this project came from two sources, my own experience and the theoretical background. I was climbing in the mountains, and I was impressed by the large scale of the structures I saw there. My sister is a social geographer, and through her I understood how many civil works were done in the mountains to prevent natural catastrophes. The engineers are not at all interested in whether humans cause climate change or not. They see that something is changing in nature, and they respond to it. I agree with that approach. Most importantly, we have the strength to change it. And we have to do that too. It doesn't matter who is responsible for it.”

To complete his project, Claudius Schulze travelled a total of 50,000 kilometres with his specially purchased aerial work platform to “I have travelled all over Europe, to France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands. The crane could rise as high as 11 meters, but I usually did not go more than 6 or 7 meters. I started in the mountains of Switzerland, where I photographed along rivers.”

Water

If you look at the images you can see a lot of water, and it seems as if the project is a warning of the rising sea level, but for the photographer that is not the case. Schulze: “The subject of my project is not only about the rising sea level and the fear of it. I am interested in climate change and natural disasters, and what is now being done to prevent this. Nowadays, many dykes, ground, concrete sea walls and dams are being built, and I have mainly looked at that. Of course, you will see many waterworks on the coast in the Netherlands, such as the Delta Works. I have travelled all over the Dutch coast. So that's why you see a lot of water in my images. However, water is not the subject itself, but part of it.”

Payment Failed

Aesthetic and sublime

According to Oskar Piegsa, who wrote an essay in The State of Nature entitled Trust not the picturesque, the style of romantic aesthetics in European art is still the most commonly used to depict nature. The Germans even have a magazine, named Landlust, that celebrates the beauty of country life. The magazine has one of the largest print runs in Germany. “The picturesque thing is defusing nature in a landscape park. In the scenic approach, nature should only be enjoyable and consumable,” says Piegsa.

Claudius Schulze plays with this cultural legacy. In his pictures, you can see picturesque landscapes: mountains, rivers and sun-drenched beaches. The images give the viewer a reassuring feeling that it is pleasant to stay in European nature. But the opposite takes place in the photos. There is no untouched nature to be seen at all. Everywhere appears to have traces of human intervention. Schulze explains: “The beauty in the photos stems from my own observation and from our culture. As dangerous and threatening as nature is now, we still have the perception that nature is always an aesthetic sensation: aesthetic and sublime, as the philosopher Kant put it. But there is a big gap between the reality of the threats to nature and the perception of nature as beauty. From this typical background of European art history, the concept of beauty enters my images. To me, we cannot call the structures changes in the landscape; they are part of the landscape itself. Nature in Europe has been designed and changed by humans for centuries. We wouldn't be able to enjoy skiing in the mountains or a day at the beach if the landscape wasn't designed.”

Ansel Adams

Schulze's photographs have a unique mix of the aesthetic style of Ansel Adams' landscapes and the critical attitude of the new topographics. “Ansel Adams photographed nature as sublime, so grand and unspoilt, and that still is the American perception of the landscape to this day. This is also due to the myth of the wild bears. I have read that more Americans die because they fall off a donkey than are eaten by a bear. But the Americans continue to perpetuate the myth of the wild bear. In his well-known books, from the series The Camera, The Negative and The Print, Adams writes in his preface that it was his job to show the beauty of nature so that people can appreciate nature. He was also a wilderness advocate in national parks. You see this approach a lot in America. There are similarities between my work and that of Ansel Adams, but then we had the countermovement of the new topographics, photographers like Stephen Shore and Robert Adams, who focused on the human-made environment. I see my work as a combination of these two major trends in landscape photography.”

Mirror?

Does Claudius Schulze want to hold up a mirror to the viewer and show that the wild landscape has disappeared, and that due to deforestation and pollution, there is no longer a primeval forest left in Europe? “I don't want to be didactic and tell with a raised finger how the world works because that creates boring art. But I hope my art can influence people's minds. The mind of man is complex. I believe that because they are aesthetic, and because they have a conflicting message, my images will encourage people to reflect. At first glance, you mainly see the beauty, but if you peak more on the details, confusion arises. you suddenly see a concrete construction. I hope people will start thinking about how and why those structures got there. In my images, I often place the viewer as the person who is experiencing the beauty of the landscape. There is no one in the photo at work. I didn’t do this to show nature as pleasant, but as a form of identification, to show that the photos are about us. We ourselves walk in that raked park called Europe.”

Photography

How does Schulze see the function of contemporary photography? “For me, photography is both an act of perception and a way of making a statement. I am not cheating my viewers. What you see is reality, but I give my vision on it. I formulate an argument with my images. Theoretical, scientific research is fundamental in my work. I spent a lot of time researching how and what I wanted to photograph. But photography is also an investigation in itself. I present my research results to the public through my images. My photo projects are similar to a master thesis, except that I present my findings in a form that scientists would not choose. I have not written any texts for this; the photos themselves are the results. We can all look at photos, so anyone can "read" my findings. To emphasize the scientific character, I have chosen to include essays by two researchers in my book.”

Claudius Schulze (1984) is a photographer and researcher. His work has appeared in numerous international publications, including GEO, Stern, Der Spiegel, National Geographic Traveller and GQ. His works have been exhibited in London, New York, Istanbul, Berlin, Rencontres Arles and Amsterdam, among others, and are held internationally in private and public collections. Schulze worked with a 4x5 inch analogue technical camera with 90, 150, 210 mm lenses, of which he used the 150 mm the most.

www.claudiusschulze.com

Claudius Schulze, State of Nature | Naturzustand, Texts of Oskar Piegsa and Prof. Dr. Thomas Glade [English / German], 30 × 36 cm, 172 p., Hartmann Books.

Order the book here: https://www.state-of-nature.eu

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)