Ice as the pencil of nature

Tristan Duke

Tristan Duke uses melting ice lenses and analogue photography in Svalbard to document climate change.

Artdoc

A black-and-white photograph shows a ship amid snow-capped mountains on an Arctic island. It appears to be a 100-year-old image taken during the discovery of the North Pole. Still, this gelatin silver contact print, titled Antigua at Fjortende Julibreen, Svalbard (Fogged), 2022, is part of the project Glacial Optics by the American artist Tristan Duke. The photograph is created using an ice lens, acting as both a creative and empirical witness to climate change—something we all know about but cannot fully fathom.

Payment Failed

Climate change was the catalyst for Tristan Duke's decision to undertake his project on ice lenses. “These issues had been in my mind, but the real push to do glacial optics was realising that we're at this hinge point in the story. When I was growing up in the '80s and '90s, climate change was still in a more theoretical space, but now people are actually seeing climate change as something that they can understand in their own lives and lifetimes.”

Duke aimed to connect different scales of time. “We face a challenge in confronting the scale of climate change because we, as humans, live a relatively short time on Earth, giving us a narrow view in geological terms. In the Glacial Optics Project, I wanted to experiment with a lens, so to speak, that brings in that larger scale—both in size and in duration—to access the deep time of the glacier and that broader scope of time.”

The Chinese Alchemist

The idea of producing his own lens from ice originated in a used bookshop, where Duke found an old book containing a passage about a Chinese alchemist who, around 300 A.D., described using a ball of ice to start a fire. “This led me to begin researching the concept of creating a lens from ice. My first experiment was to replicate the Chinese alchemist's experiment, using an ice lens as a magnifying glass to ignite a fire. However, I also discovered Japanese technology for making cocktail ice, which is like an ice press. The ice is warmed in a metal mould; a chunk of ice is placed between two parts, melting into the desired shape. I made my own custom ice presses in lens shapes, and that's how I managed to create these lenses from glacier ice.”

Duke experimented with different lens shapes and focal lengths. He developed a kit that allowed him to assemble front and back surfaces in different configurations. “I can recombine different pieces of the ice press in various ways and flip them. They have different curvatures machined into their sides. I can produce lenses with different focal lengths by reassembling their parts. I can make a range of lenses for different needs at any time. I believe this is the only camera system where, if you want to change lenses, you can reshape the lens on the spot. And if the ice lens gets a scratch, you can remelt it.”

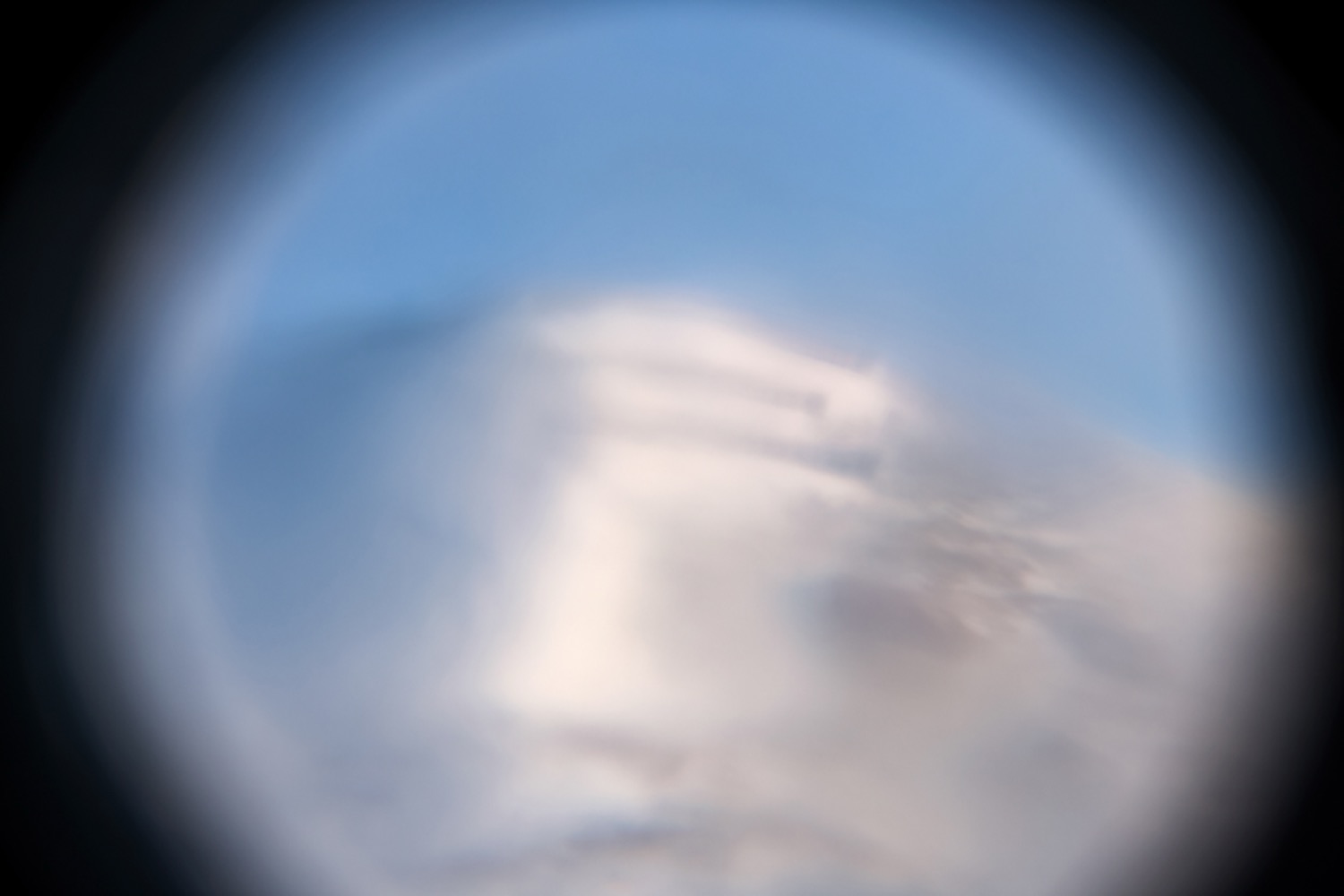

To obtain a sharp image with the ice lens, the ice should be actively melting. “When melting, the ice lens forms a liquid envelope of water over the surface, and the surface tension of this water makes the lens perfectly clear and smooth. This is analogous to the function of tears on the surface of the human eye. Without that wetted surface, the ice does not make such a good lens. To make matters worse, when it gets below zero, the ice lens tends to frost up.”

I made my own custom ice presses in lens shapes, and that’s how I managed to create these lenses from glacier ice.

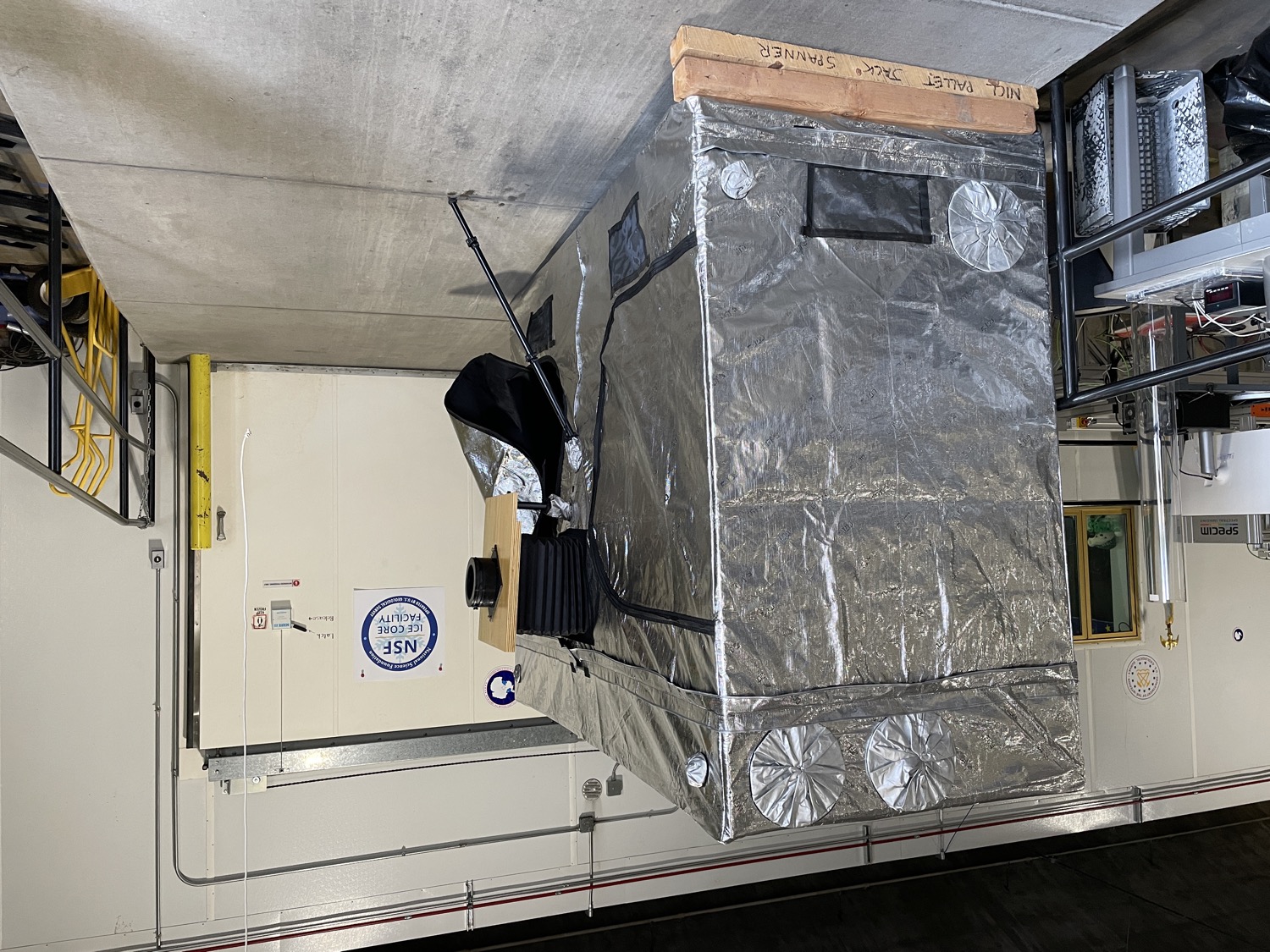

Camera obscura

Just before exposure, Duke inserts the handmade-on-the-spot lens into the fixture of his foldable, tent-like camera obscura. The focal lengths of his ice range from 1000mm or longer (given the massive scale of his camera, this corresponds to an angle of view comparable to that of a 50mm or longer lens on a standard full-frame camera). Inside the tent, he hangs the paper negative, which can measure up to 2.5 meters in length, on the opposite side of the lens. After exposure, he wraps the large sheet of paper negative and brings it back to his studio to develop. The positive print is made by placing the negative face down on a new sheet of photo paper and exposing it to light. In this way, he can print small editions, which is challenging due to the very delicate dodging and burning required to achieve the desired tonal ranges. “Because the contact print is facing down, dodging is a little tricky because you're doing it blind. You have to put considerable planning into it. I have special templates and setups where I plan everything.”

Spitsbergen

For his project, Tristan flew to the Norwegian Arctic island of Svalbard, part of the Spitsbergen archipelago named by the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz. Svalbard Island, mainly covered by ice, is situated about 565 km north of Norway and is warming at an alarming rate, six to seven times faster than the global average, making it a frontline for climate change, with dramatic temperature increases, rapid glacier melt, disappearing sea ice, and thawing permafrost, leading to ecosystem disruption. “I travelled in the very beginning of April, for the dawning of the polar day. It's still a freezing time of year. I was very nervous about whether the setup with my lenses would work at all. It turned out in a bitter irony that when I arrived, Spitsbergen had a climate change-induced heatwave, and the temperatures were far above normal. When I was there, the temperature hovered around 0°c. Thus, this was at the freezing point. I quickly discovered that if I dipped my lens fixture into seawater, the water was sufficiently salty that it would cling to the surface, wetting it and inducing some melting, even though we were hovering just below freezing. If it were too cold, that still wouldn't have worked.”

But aside from the irony, climate change made the project possible, which, for Tristan Duke, offered a poetic notion that the lens must be melting for it to see. The technique involving the ice lens is only feasible with melting ice, creating a double witness: one from the essence of photography and another from the lens's melting. “The ice lens bears witness to our current moment of rapidly melting glaciers. These images are infused with a sense of deep time and the things we're losing now. I often leave a quite large vignette around the final print so that you see the full image circle. These photographs not only capture the scene but also depict the lens itself. I want to remind people that we're looking through this aperture of ice.”

The big picture

Even though we are all scientifically well informed about global warming, it is often difficult to form a mental image of the process, aside from the almost clichéd images of solitary white polar bears. Scientific reports with diagrams don’t produce a wider picture. “Biologically, we have evolved to survive within a local frame –adapting and responding to the environment we encounter directly. But we have become a more global species; not only do we get information from around the globe almost instantly, but our modern lifestyles also have wider impacts on the global environment. And yet we're living within the biological programming of a local species. This is one of the major challenges we face: reconciling our daily lives and lived experience with the increasingly big picture we're confronted with.”

It was a significant part of his motivation for taking this trip to Svalbard. “I really felt the responsibility, as an artist, to try to create images that convey the urgency of the climate crisis in a new way. I believe art has the power to communicate something beyond the obvious. It's like the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, where sometimes the right image can resonate and say more than words or data ever could. I wanted to see whether art might be a way to make people curious about climate change from a different perspective, because I believe we're desensitised. We build a thick skin around this issue.”

Annual layers of ice

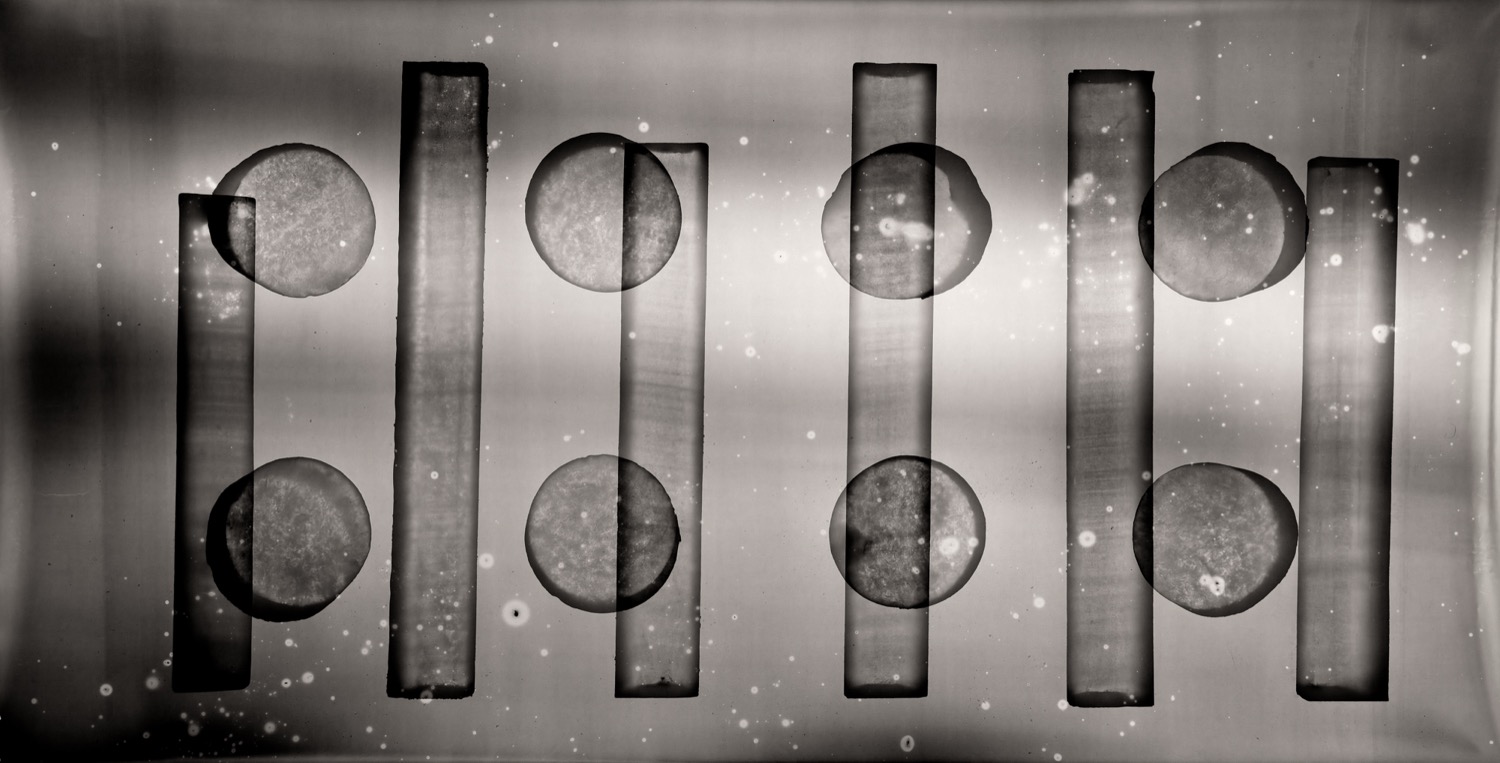

Duke also visited the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility and other climate science laboratories, where researchers study glacier ice to understand Earth’s climate history better. At these laboratories, he produced photograms of ice cores, samples of ice extracted from deep within glaciers. “You walk into this huge warehouse-sized freezer, filled with racks and racks of tubes, each containing a one-meter-long cylinder, a sample of ice. The ice cores contain strata, annual layers, which are very much like tree rings. They depict the glacier's growth over time. It's like having a time machine where the scientists can go back and collect a sample of air from millions of years ago.”

As a visiting artist, Duke used the ancient ice as a lens in his darkroom tent, capturing ice-lens images of climate science in action. In his Ice Core Studies series, he also placed the excavated ice cylinders on sensitive paper, creating photograms of the historical patterns within the ice that reveal the geological evolution of oxygen and carbon levels in Earth's history. “What's fascinating is that you not only get the silhouette of the ice, but because the ice is transparent, you also see light passing through it, and the photogram records the strata in the ice, the annual layers—precisely the layers that scientists study. This was an exciting discovery. It was thrilling that these images convey this essential climate science story and align with the original vision of the glacial optics project. In some ways, these photograms are the most formal distillation of the idea of an ice lens, because, of course, you still have light passing through ice to be recorded on film. But in this case, the ice cylinder itself becomes the full subject.”

The pencil of nature

The images of ice cylinders representing the geological strata might be considered surrealist, even though they are essentially realistic. “I recently saw the big Man Ray show at the MET in New York. My Ice Core Studies certainly resonate with his photogram work, but perhaps more relevant are Fox Talbot’s photogenic drawings, especially his photogram prints of leaves and other botanical subjects. My ice-core studies may appear abstract and formal, but they are also highly scientific. My work is often situated between the worlds of art and science.”

Fox Talbot, the inventor of the calotype process, which also used paper as a negative, titled his book The Pencil of Nature, stating that it was not he himself but nature that made the picture and that he was essentially the artist. “Talbot’s appellation refers chiefly to photography’s automatic action –the image appearing on the film, without needing the hand of an artist to render it. In many ways, Glacial Optics extends the notion of the ‘pencil of nature.' By creating a lens from the very landscape, and invoking a glacial gaze, nature becomes the camera and the photographer too.”

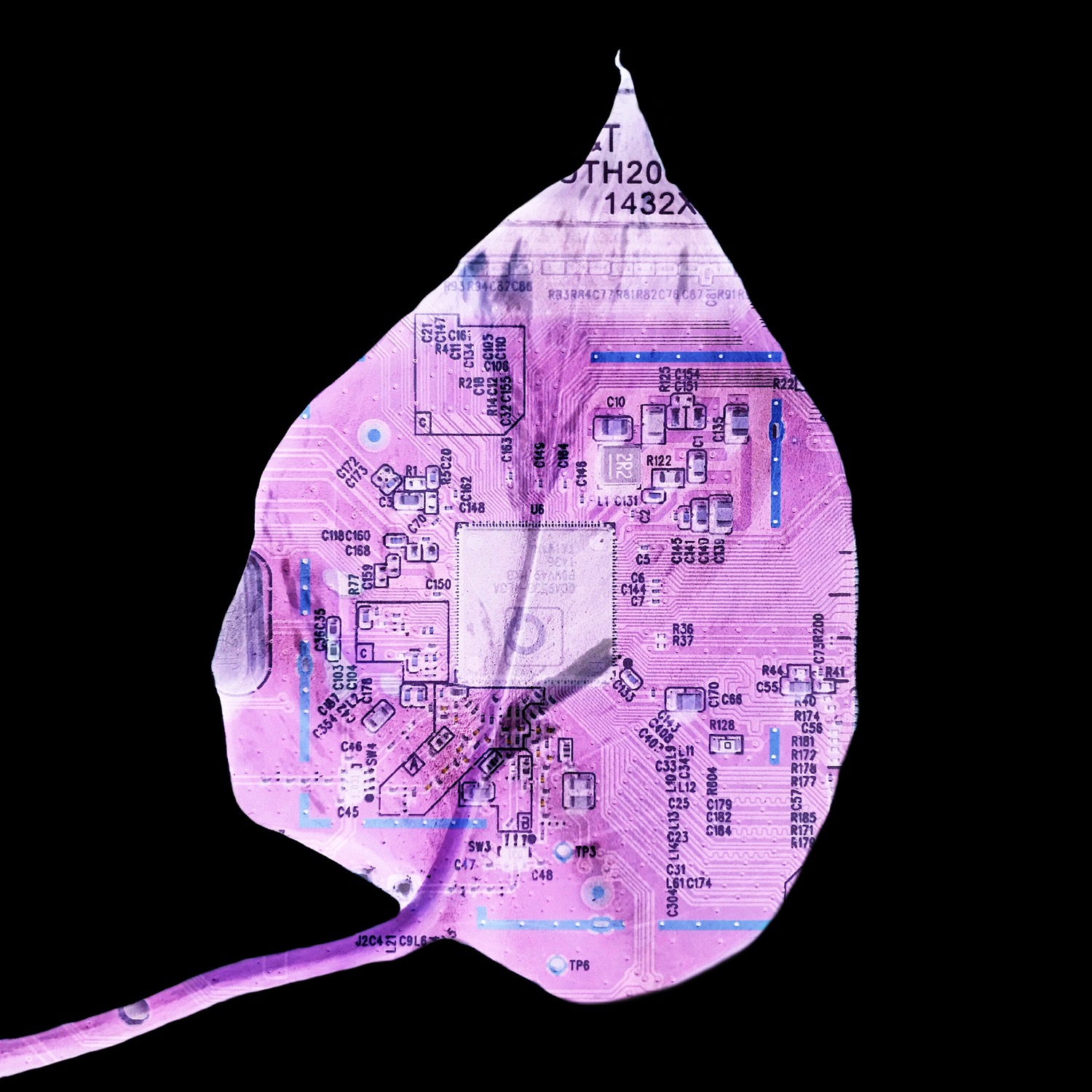

“Photography was more discovered than it was invented. The light-recording action of silver salts is a natural phenomenon, and the resulting photograph can be thought of as a kind of fossil image, a photo-fossil formed in silver. This project seeks to redefine photography as a land-based practice. People often overlook that the basic materials of photography are derived from the land. Even the most modern digital camera contains rare-earth elements and silicon. And the lens itself is made from silica, from sand.”

With this project, I'm venturing into the world with this fragile, melting glacial ice lens.

Photography as art

There is still a distinction between documentary photography and the so-called ‘fine art’ photography. Still, they are the same, sharing the essence of photography as a subjective and transformative documentation of reality. Tristan Duke does not distinguish between the two visions, referring instead to the image’s aura. “What Walter Benjamin means by aura is similar to a sense of provenance. It's like the sense that a physical object has a history. Once you start reproducing images, the connection to the material is broken. The Glacial Optics project seeks to capture something of the aura of the climate crisis –or at least, through multiple layers of indexicality, create images that are deeply connected to the material reality of this moment. These negatives were transported to the Arctic, hauled across the ice, pinned up in a tent, and then a piece of glacier ice was shaped and placed in front of them, and the shutter was opened. The images speak to that action in space and time.”

His works practically demonstrate that photography is a time-based medium. Duke challenges the mechanical repeatability of photography, questioning traditional ideas. “I inject some wildness into the process to make photography more feral, to make photography more of nature. It is an inversion of the romantic gaze, because in the romantic gesture, you're depicting nature as this unbridled, cataclysmic force, untamed and indomitable. With this project, I'm venturing into the world with this fragile, melting glacial ice lens. It's a fragile nature that is bearing witness to an indomitable human world full of cataclysmic extremes.”

Curiosity and creativity

Intentionally, his work is non-polemical, as Tristan Duke’s reference is not a political statement but an artistic wonder. “I'm not starting with a scientific or political climate message necessarily. The initial impression of my work is an invitation to curiosity and mystery, because if we fail to address climate change, it will be a failure of imagination. We need to become inventive. We need to be creative. My intention with this project is to lead with curiosity and creativity to prompt people to examine the situation. Because there is too much polarised politics around this topic. Confronted with a heartbreaking image of climate devastation, people tend to jump into their comfort zone. If you already think that climate change is a hoax, then you might think it is propaganda and ignore it. Or if you are already sympathetic to the notion of climate crisis, you might feel depressed and want to look away. Both of those positions shut our eyes. I want to open the imagination with curiosity.”

About

Tristan Duke is a Los Angeles-based conceptual artist whose work explores perception, deep time, and human relationship to space and environment. Known for developing experimental techniques and building his own artist-technologies, he often engages directly with light as a medium –through immersive light and space installations. Blending interdisciplinary research with expeditionary fieldwork, much of Duke’s work emerges through direct collaboration with scientists. Duke is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including the LACMA Art + Technology Lab Grant, the Nevada Museum of Art Peter E. Pool Research Fellowship, and the CLIO Award. His work has been exhibited widely, including at SITE Santa Fe, LACMA, C/O Berlin, MASS MoCA, and numerous other venues. His book Glacial Optics was published by Radius Books in July of 2025.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)