Iranians’ ordinary grief

Parisa Azadi

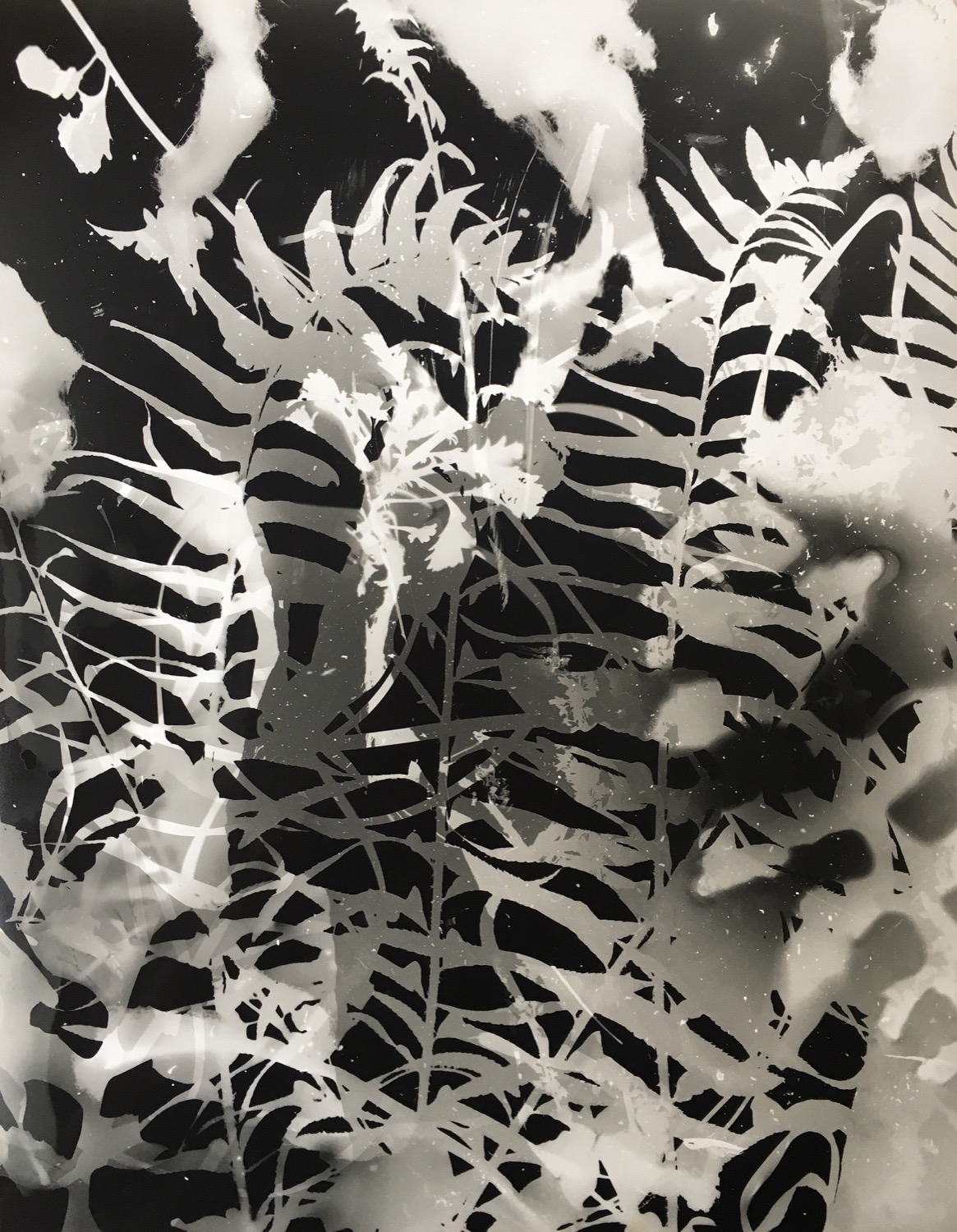

Iranian-Canadian photographer Parisa Azadi returns to her homeland after decades, capturing intimate emotions that mirror its challenging times.

Artdoc

Aside from the difficulty in understanding the complex emotions of the Iranian people, Iran is frequently and sometimes unjustly perceived as an insecure nation, and this makes travelling to that nation complicated. Iranian-born Canadian photographer Parisa Azadi returned to her homeland after decades of being away and found private moments of inner emotions reflecting the country’s challenging times. In her personal Ordinary Grief series, Azadi captured the invisible threads that connected her with the people she met during her travels.

Published in issue #3 2024, Invisible Threads

Payment Failed

Growing up after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Parisa Azadi migrated to Canada with her parents as a young child. The family longed for a better life as Iran went through a dark time in the mid-1990s after the exhausting Iran-Iraq war. “I grew up in a repressive social environment. We had to live through the aftershock of the Revolution, which radically changed daily life for Iranians. We lost many of our personal and social freedoms overnight. The State controlled the most private aspects of our lives. For example, the hijab became a compulsory dress code for women. Growing up, I had a heavy experience with violence and grief. We learned to hide behind walls to protect ourselves from the outside world. We felt exiled even before leaving our country.”

The voice of photography

Azadi became a photojournalist after studying politics and sociology in Vancouver. She needed an emotional outlet to cope with her childhood traumas and a creative tool to celebrate her newfound freedom. “The religious trauma of my childhood had shaped my inner world. Assimilating as a survival tactic, I stopped speaking my mother tongue, Persian. I found myself struggling with a profound sense of un-belonging that I carried with me throughout my adult life. Photography gave me a voice and a means through which I could discover the world and tell stories about complex issues through images. My personal history inspires much of my work: political violence, social injustice and radical resistance. Photography allowed me to look at the world through my lens, question it, engage with it and find my place in it.”

The learning path of Uganda

Working for a local newspaper, Parisa Azadi covered various topics and activities like political events, drug addiction, health issues and homelessness. The assignments gave her the required experience since she did not have a formal education in photography. At the beginning of her career in 2010, she moved to Uganda and worked as a photojournalist. “I took a leap of faith and moved to Uganda at age 23. I was young and very sure of myself. I knew the kind of stories I wanted to work on and the direction I wanted to go in my career. I first worked for a local independent newspaper and eventually worked with the Associated Press and other bigger publication agencies. I covered every major political event and humanitarian crisis in the country, from suicide bombings and presidential elections to gender-based violence.” The broad experience allowed Azadi to develop her visual aesthetics for her work later in Iran.

Gradual Change

After 25 years of absence from her motherland, Azadi visited Iran in 2017, after which she returned regularly to produce her ongoing personal project, Ordinary Grief. Returning to her native country, she was stunned by the openness of the Iranian people. “For example, I love this image I made of the two little sisters on the beach; it’s a tender and honest moment. I was struck by their innocence, what they were wearing and how free they felt. The portrait reminds me of the significant changes that have happened in Iran since my childhood. I grew up in a very dark time in Iran’s history when children could not dress freely in public spaces, even at the beach.”

I grew up in a very dark time in Iran’s history when children could not dress freely in public spaces, even at the beach.

The photo of the two sisters on the beach appeared to be an icon of the gradual change in Iran. “I found moments of lightness and private moments creeping outdoors and becoming more noticeable. I saw Iranians challenging traditionally acceptable boundaries, actively creating a new future for themselves and building cultural spaces away from the authorities.”

Even though Iran is still a traditional country in Western eyes, Azadi saw the little changes as significant steps towards an open society. “I witnessed Iranians pushing the boundaries of what is traditionally acceptable. It was a collective rebellion: allowing your children to wear bathing suits and feel the wind in their hair, taking your dog to the park when dog-walking was banned, or unmarried couples being affectionate with each other publicly. These small acts of rebellion have pushed social change in public spaces in Iran.”

Ordinary Grief

Despite the gradual openness of Iran, Azadi was met with a range of ordinary, daily grief by the Iranian people. The photo of the two girls in an apartment, one lying on a sofa, the other looking out of the window despondently, is a striking example. “Over time, the feeling of grief became the centre point of my work. In Persian lore, we say, grief is a familiar place, and often, our stories do not have happy endings. When I was photographing in Iran, there was always this feeling of grief floating in the background. You could tell by people's body language and how they stared off into space or gazed out through the windows. I took photographs of Nesa and Yasaman in the early days of the pandemic when the political climate of Iran was changing quickly. There was massive inflation; many Iranians were becoming poor overnight. Nessa (lying down) was living out of her suitcase after losing her job and apartment. Yasaman postponed her plan to move abroad due to financial challenges. I caught them gazing quietly out the window, suspended in this unresolved circumstance. They lacked a sense of urgency in their lives and destinies. I used photography to process that trauma and anxiety. It was about understanding the experience of imprisonment and living in isolation.”

When I was photographing in Iran, there was always this feeling of grief floating in the background.

Witness of private feelings

Parisa Azadi had to find a way to capture moments in which the people she met revealed their private feelings of sadness through gestures. “Finding the right atmosphere to capture inner grief is not like photographing an object, like a chair. I used photography to process my experience in these quiet, in-between moments when people were self-absorbed in grief. Gradually, I saw more of these moments at parties between the dancing and conversations. It was never a simple joy or real moment of happiness. I felt a huge burden of responsibility—how could I help people understand what was happening here? It's very intuitive work. It was about letting myself be vulnerable and allowing myself to be a witness to these dire moments.”

A love letter to Iran

The Ordinary Grief series is a social and personal project because Azadi saw herself as a photojournalist and photographic artist. “The work became a love letter, but in some ways, it became a farewell love letter because of the fragility of life in Iran. People in my photographs continue to face severe economic and political stagnation. Some have lost jobs or livelihoods, others have immigrated, several have died tragically of COVID-19, and some are in prison for their work and activism.”

Ordinary Grief is an archive of Azadi’s journey to understand Iran and a presentation of stories about Iran to an international audience. “Much of my work aims to counter easy stereotypes and convey a more complex and contradictory humanity—ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. My imagery, though seemingly straightforward, is necessarily ambiguous. It aims for the poetic, subtle metaphors and ambiguity to speak of politically sensitive topics and push the boundaries of Western understanding of the Global South.”

Azadi’s photographs show invisible threads of connection between the people’s arduous lives and the photographer’s emotions. “I allowed myself to be vulnerable, gaining access to people’s stories by sharing my own. Initially, I tried to hide my ‘foreignness,’ but my accented Persian outed me as a Westerner. Over time, my accent became a point of entry, instigating conversations and facilitating connections. I tried to find moments that reminded me of my childhood, made me question things, and surprised me. You can see this in the image of the young couple out on a date. I was curious about what it was like to fall in love with somebody with all the restrictions and how unmarried couples push the boundaries of the law. I also wanted to get closer and come to terms with Iran as my home, as a place where I could exist. I wanted to confront my shame about my own identity.”

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)