Notes on the Occupation

Andrej Verzola

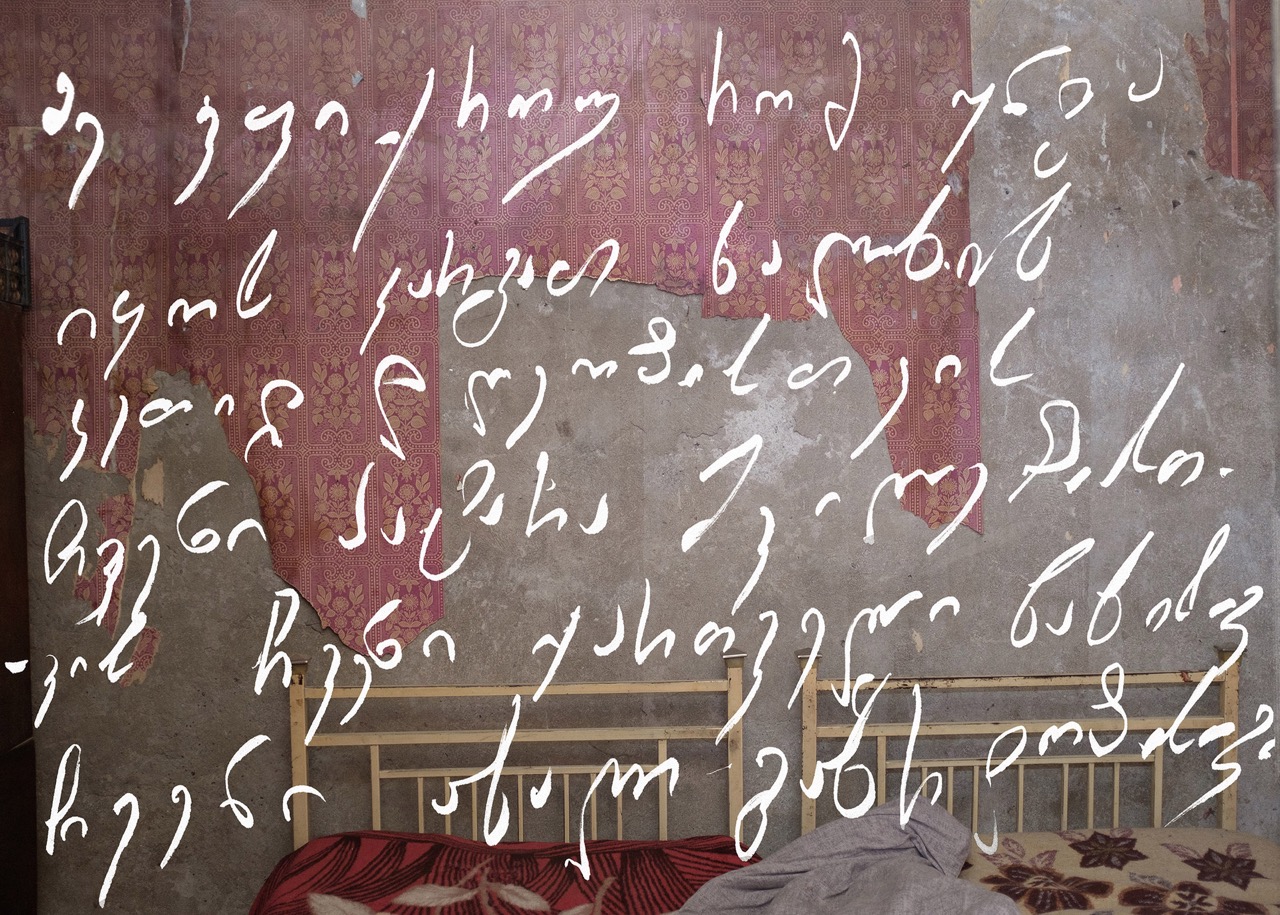

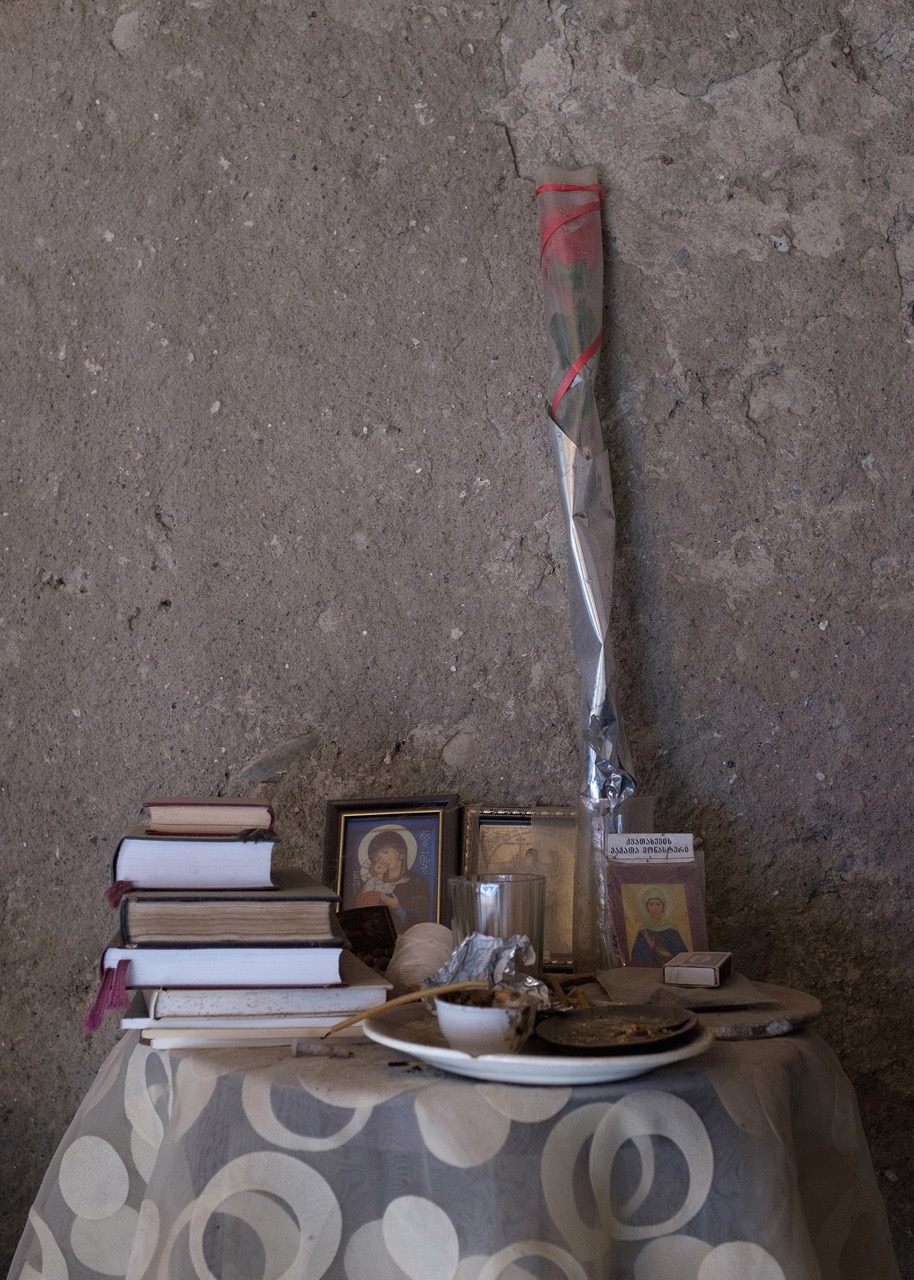

This project explores lives scarred by Russia’s occupation of South Ossetia.

Artdoc

This project explores the human cost of Russia’s occupation of South Ossetia since 2008. Along the tense contact line, Georgian villagers face daily fear, arbitrary detentions, and violent intimidation. Through personal stories of those imprisoned for crossing invisible borders, the work of Andrej Verzola reveals a stark reality of life in the “Zone of Fear.”

Payment Failed

Andrej Verzola: In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia and occupied two regions, including South Ossetia. The line of contact between Georgia and South Ossetia stretches approximately four hundred kilometres, with over ten thousand people residing in its immediate vicinity on the Georgian-controlled side. The population of this so-called "Zone of Fear" mostly consists of farmers residing in small, semi-abandoned villages. Following the war, many residents of these lands fled to Tbilisi or Gori, but some chose to remain, feeling deeply connected to their land. Locals suffer from systematic encroachment by Russian troops, who often erect “border” fences overnight, seizing pastures, churches, cemeteries, and water sources. This strategy aims to intimidate and disconnect them from their roots. Moreover, since 2008, approximately 3,500 cases of illegal detention of Georgian citizens by Russian and South Ossetian authorities have been recorded.

My project documents the stories of some Georgians who were detained near the occupation line by Russian border forces and imprisoned in Tskhinvali. Over the course of a year and a half, I travelled through these regions, speaking to those for whom detentions have become routine. Some were arrested once, while others multiple times—one man was captured five times. For them, life is divided into “before” and “after” the arrest: a trip to a once-familiar pasture or a visit to the grave of a loved one could lead to a new detention and prison term. Many have endured brutal beatings, and some have lost their lives for crossing the occupation line.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)