Portraits of North Korean Defectors

Tim Franco

Tim Franco made portraits of North Korean Defectors

Artdoc

For North Koreans, it is virtually impossible to escape the militant and brutal regime, but still, few people manage to cross the frozen river along the border with China. Most defectors finally end up in the neighbour country South Korea, after a long and hazardous journey across China and other countries. Photographer Tim Franco, based in Seoul, wrote down their chilling stories and made portraits of the 'unpersons'.

The North Korea subject matter is vast and inexhaustible. More and more photographers have found their way to North Korea to photograph the orchestrated 'daily life' of the country, mainly in the capital Pyongyang. Some photographers get access to more areas than the average tourists' are able to highlight, like Carl the Keyser in his book DPR Korea Grand Tour. Others manage to highly stylize the vision of the most forbidden country in the world, like Eddo Hartmann in his book North Korea. But not Tim Franco. He realizes that it was not easy to come up with another version of new, never before seen images of the journalist-locked country. Living in Seoul and hearing about the many defectors living there, Franco decided to portrait them and listen to their blood-curdling stories.

"To start with, I found the theme of North Korea too easy, so for a long time, I disregarded it. But in Seoul, I lived 60 kilometres from the border, and I knew close to nothing about North Korea, except what you see on the news. So, I wanted to know more about this utterly locked country. The obvious way was to visit North Korea, but most people who go there take the same obligatory pictures. Apart from that, some good projects have been done there, already like that of the Dutch photographer Eddo Hartmann. I could not see how I could do things differently."

Payment Failed

Defectors in Seoul

When Tim Franco talked to journalists in Seoul, he realized that there was a community of defectors of North Koreans there. After conducting an investigation, he was able to speak to some of them. "They could tell the stories that I was looking for. But it is hard to find defectors who agree to talk and tell their stories and to have their photographs taken. If you want to go to their house, it is almost impossible. Many of them still live in fear."

Many of them still live in fear.

The first people he interviewed were regular defectors who had already talked to the media. "I wanted to meet defectors from different backgrounds and different stories; I wanted to talk to people from poor backgrounds but also people from the elite class. And I wanted to hear the different reasons for defecting. I also needed to create a safe environment for them to make the portrait and have an interview. Happily, I found a press centre in downtown Seoul."

Many defectors leave together with their families because they know it will be terrible for their family if they leave them behind. There are more defectors in China than in South Korea. "Defecting to China is very hard and dangerous, but it is not viewed by North Korea as bad as defecting to South Korea, which is the ultimate enemy of the North. That is why many defectors make their families believe they are in China. That was why many people don't want to speak to the press. People that have no family back in the North are less afraid, and they allowed me to photograph them."

Stories

Tim Franco interviewed all the twenty-five defectors he photographed. "In writing their stories, I focused on different themes, like how they escaped or how their life was in North Korea or how they had to adjust to the South-Korean lifestyle."

It was obviously not possible to fact-check or verify their stories. "In South Korea, it is customary to pay the people you interview, so normally people tend to exaggerate or change some parts of their stories. I was cautious about that, and I refused to pay them. In some cases, I found the stories, according to my research, a little bit too unbelievable to put in my book. And some people told me things that they did not want to be on the record."

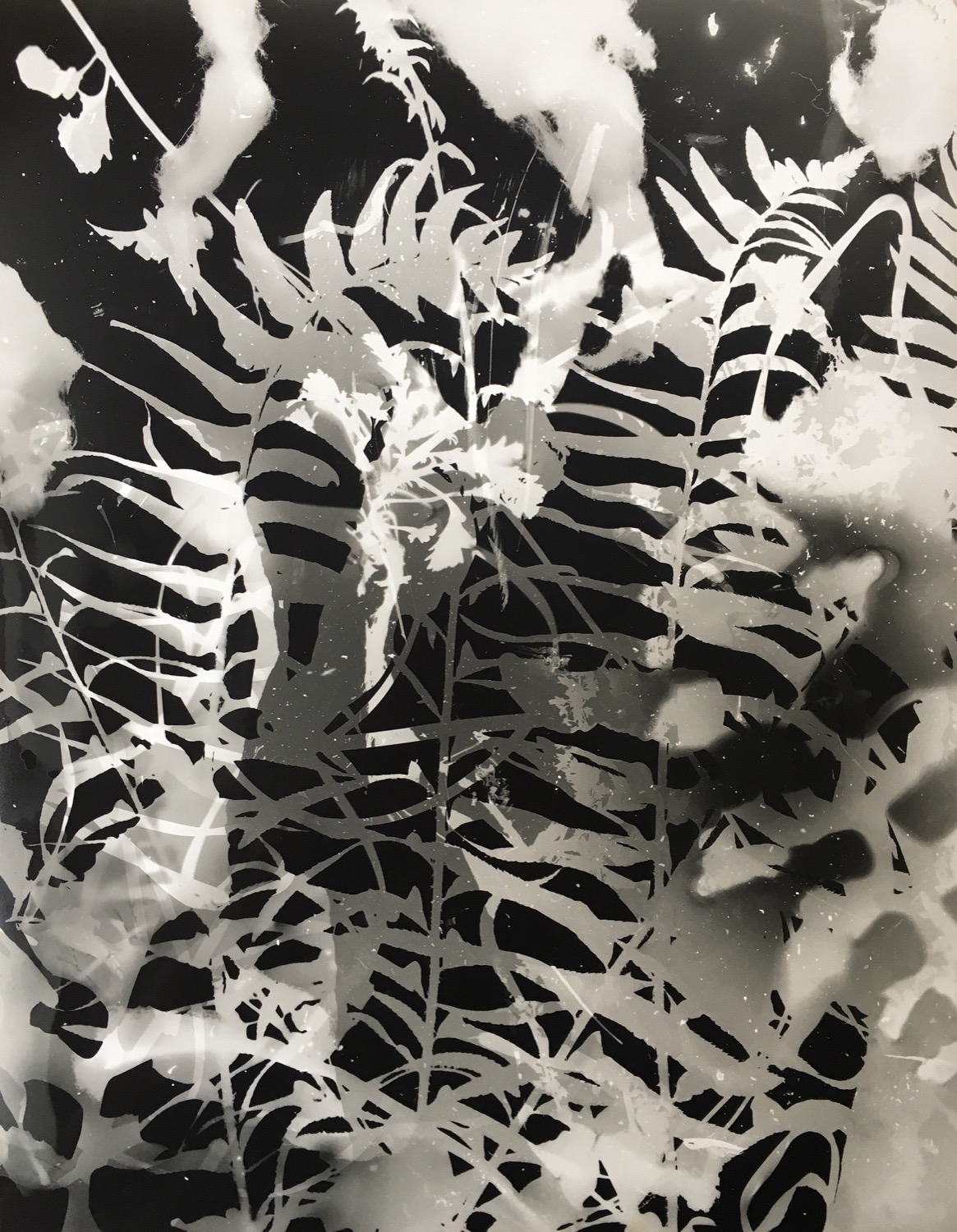

Polaroid negatives

The portraits are made on Polaroids Fuji peel apart, which give them a worn and old look. Tim Franco explains: "The Fuji is - unlike the Polaroid 55 - not made to preserve the negative, but if you carefully wash the negative, you can use it and scan it. But you are not supposed to do that. The concept of my approach was that my use of the negative reflected their situation. Because I was using the negative 'illegally,' it was a way to express the fact that they were not supposed to be in South Korea. If you do this process of cleansing the negatives, you get scratches and chemical spills. That was a way to express the fact that they fled from the North to the South, which is a long and complicated process. So that scratchy, dirty, imperfect negative was their story."

Long distances

When Franco completed all the interviews, he had a better understanding of how they escaped. "Most of the defectors first go to China, and after that, they have to find a country that recognizes their refugee status, like Thailand and Mongolia. It is extremely difficult for them to travel from China to one of these countries. They all want to reach South Korea, but they have to travel far to reach their neighbour country. In China, the police are looking for them, so they get easily arrested and send back to North Korea, where they end up in a labour camp. I, therefore, made landscape pictures, and underneath the photos, I put the distance to their final destination. I started in North Korea, and the distance was often only 60 or 100 km away from Seoul. In Bangkok, it was more than 3000 km. I especially photographed the border river between North Korea and China and the border between China and Laos and Mongolia. To reach Mongolia, you have to cross the Gobi Desert, which is extremely dry and dangerous. When you open the book, it starts with landscape pictures of North Korea because that was where I wanted to start from. At the end, you see landscape photos of South Korea."

Tim Franco is a French Polish photographer born in Paris in 1982. Formerly based in Shanghai for a decade, he documents the incredible urbanisation of China and its social impacts. This body of work was published as his first Monography Metamorpolis - the conclusion of five years of work about the rural migration in the fastest urbanising city in the world: Chongqing. It was during this time that Tim developed his style of working mostly on analog camera and trying to bring a minimalist aesthetic to documentary photography. In 2016, Tim Franco moved to South Korea where he started working on a long term project about North Korean defectors. He has been collaborating - amongst others - with Time Magazine, Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, National Geographic, Le Monde, Geo and 6 Mois.

http://www.timfranco.com

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)