The humanity of a dehumanised people

Sakir Khader

Dutch-Palestinian Sakir Khader documents Palestinian lives, honouring his cousin killed by Israeli forces.

Artdoc

As a child, Dutch-Palestinian photographer and filmmaker Sakir Khader would visit the West Bank every summer to see his family. When he was 11, he often played with his similarly aged cousin Kosay. After young Sakir returned safely to the Netherlands, he learned that his cousin had been shot dead by the Israeli army for no apparent reason. This tragic event, symptomatic of Palestinian life since the founding of the state of Israel, referred to by Palestinians as the Nakba (the catastrophe), motivated Khader to become a photographer. He wanted to capture the unimaginable suffering and difficult lives of Palestinians in the many enclaves in the West Bank, where ethnic violence is an everyday reality.

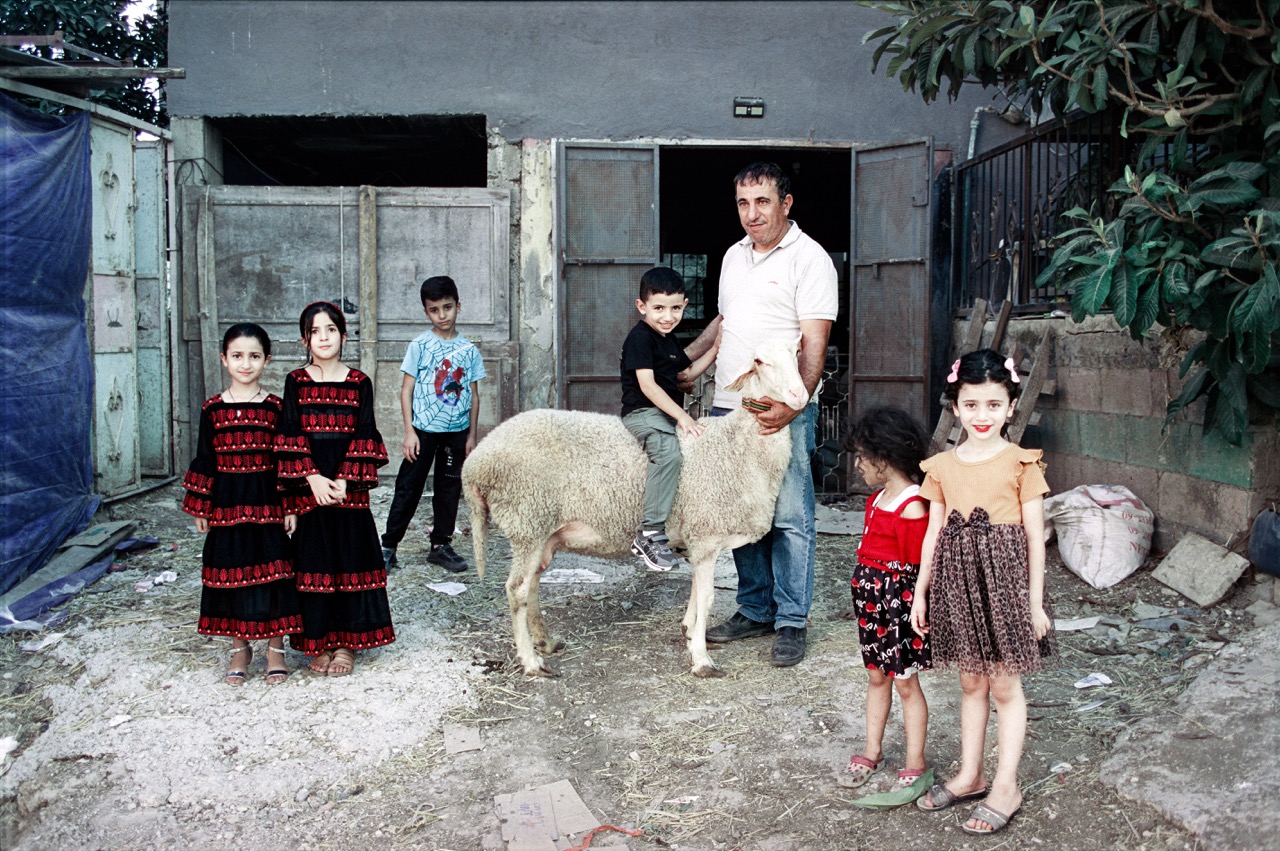

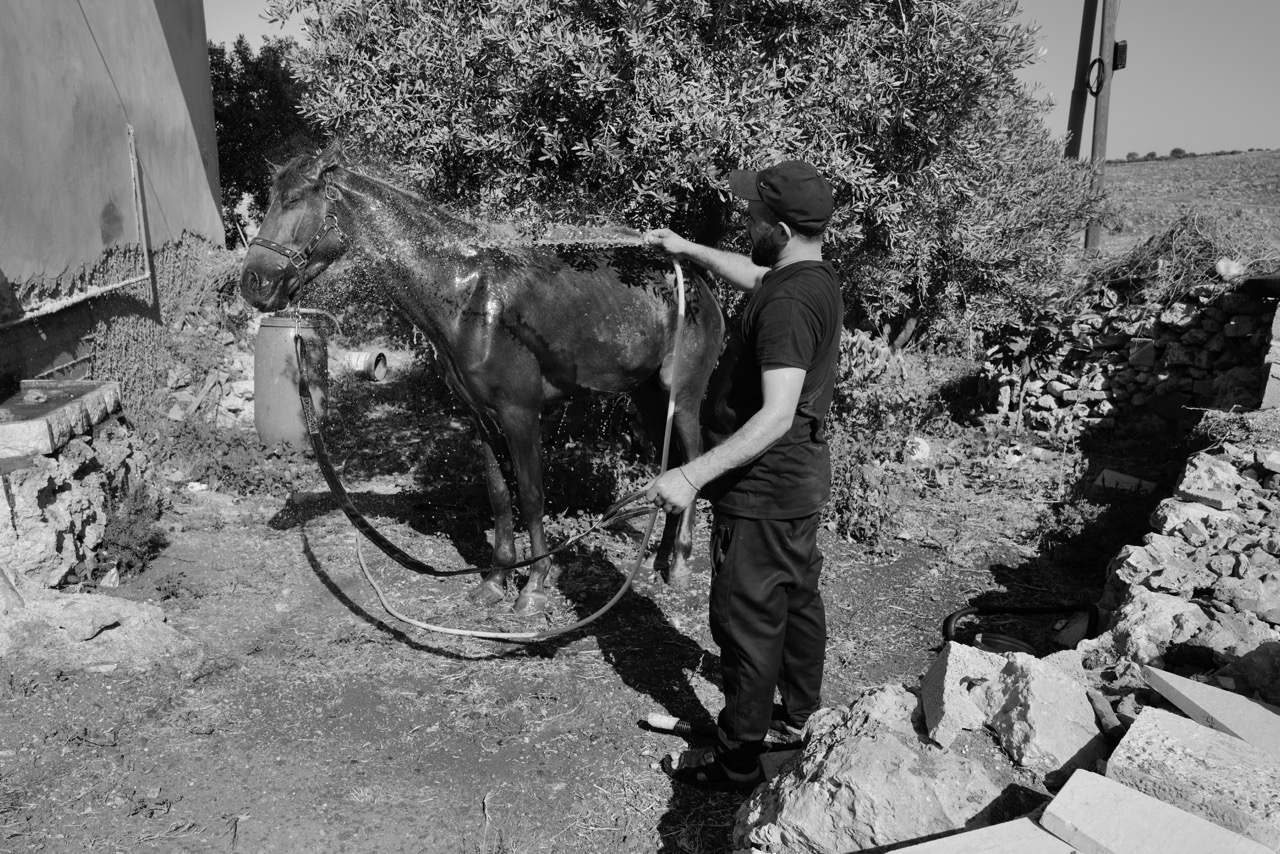

Payment Failed

Despite the dire circumstances faced by the inhabitants of Jenin, a Palestinian town in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where Sakir Khader took numerous photographs, we also witness everyday scenes from life. Two cheerful girls in traditional costumes, a man on a motorbike, a young man at the gym, an older man smoking on his bed, a barber working outdoors, and a child sitting on a sheep. These images convey the atmosphere of a relaxing summer day. However, at the same time, some pictures unveil a stark reality: the Israeli army's ongoing siege, humiliation, and intimidation. You see the dead and wounded, where life and happiness once thrived. Kader explains his position as a photographer: “I never chase the news. I like to capture everyday life. I don't photograph events where forty other photographers are chasing images. Then you become part of a database from which the media have forty other choices. One hundred deaths in Gaza are just statistics. But I have been photographing all my life in specific neighbourhoods and cities where I know everyone by name. I can picture those people in their most vulnerable positions and intimate moments. They are the same individuals who later perish in bombings. They will always be remembered through my photographs as people who lived and loved, rather than just numbers in an archive, without knowing their faces. This is how I humanise the people in the photos. I don't need to convince anyone that they are people I photograph, but they represent my country and my people. These people were always represented by Western media in a certain way.”

I don't need to convince anyone that they are people I photograph, but they represent my country and my people.

Humanity

Humanity is not merely a general concept about people on Earth. It is also an ethical notion that describes how humanity constitutes a network of individuals who support each other with love and compassion, grounded in justice and upheld by human rights. The whole world now knows that this is not the case in Gaza, where a genocide is taking place. In the West Bank, the situation is not as severe yet, but it is progressing in that same direction. This is what visual storyteller Sakir Khader is concerned about daily. He wrote on his social channels about the commemoration of World War 2: “So much has already been written, so much said, and yet it all seems only to deepen the ache. Because no matter how loud we cry out, no matter how clearly we write, the suffering of those we love in the homeland continues unabated.

Not that I ever believed words alone could stop butchers at their work. But this time—this sustained and deliberate cruelty—has made something unmistakably clear: the world we once ‘believed’ in no longer exists. And when I say, “the world,” I don’t mean the ones who are awake—those who witness and resist. I mean the systems: the states, the institutions, the sleepwalkers so drunk on delusion they mistake silence for neutrality and power for justice. The world has acclimated to the normalisation of mass killing, to Israel’s unchecked aggression. In Gaza, it is not history. It is now. Every minute, another family. Another child. Another father. Another mother. Another home. Another neighbourhood. Again. And again. Starvation. Displacement. Bombardment. And over it all, the quiet arrogance of a world still convinced of its own moral superiority. The silence. The rhetorical acrobatics. The pious statements. The lies. “Never again” was never meant for us."

When we speak to him about his writing, he explains in his extremely calm voice that when he can't photograph, he starts writing to express his anger and sadness about his homeland, Palestine. “What I want to tell, I photograph on location, but when I can't photograph, I write. I worked as a writing journalist for many years. In my forthcoming book, I will add much written text because words and images complement each other very well.”

Mothers and sons

In spring 2025, at the Amsterdam photography museum Foam, Sakir Khader held an exhibition titled Yawm al-Firak, Arabic for Day of Farewell, which recounted the tragic deaths of nine Palestinian boys and the responses of their mothers. In this narrative, Khader drew upon the literary Arabic tradition, linking it to personal stories. Portraits of the sons adorned the exhibition while portraits of their mothers faced them on the opposite wall, many of whom lived in the (now demolished) refugee camp in Jenin. Khader has been documenting daily life intertwined with death for years, where ‘goodbye’ is the common thread. “They are people who sacrifice for freedom. We call such a person a martyr, but internationally, that is seen as glorifying death, while for us, it has the meaning of witnessing suffering. I show who these young men are and the love of mothers for their sons.” The viewer is not spared: the images of the deceased are shocking to witness. However, according to him, this is the harsh reality of everyday life.

Subjective stories

It is often said that photojournalism should adhere to the code of objectivity as part of journalistic writing, examining the situation from both sides. However, in today's photographic practice, this perspective seems outdated. Presently, documentary photography serves as a more subjective form of storytelling, as only in this manner can the complexities of humanity be depicted. During a notable television broadcast in the Netherlands, Khader was asked why he did not include the other side of the story, to which he replied with restraint that, with his beard and dark complexion, he would be immediately shot in the head if he travelled to an Israeli settlement. “I am a subjective storyteller, an ethical photographer, who photographs with empathy for his subject. The Western media have demonised and dehumanised my people. When I capture people on camera, it is important that their eyes make contact with my eyes. I need to know that people are comfortable with my presence and how I capture them. The camera is a permanent part of me; people know me in the Palestinian territories. Sometimes I leave the camera in the bag and wait for the right moments.’

Like birds in a cage

A poignant photograph features an eight-year-old girl amid the rubble of a bombed-out house, dressed in a jumper adorned with the word ‘heart’ in ornate letters. She has lowered her eyes and gazes thoughtfully at the ground, contemplating what her life may look like in the future. Khader refers to her as an angel, but this angel confided in him that she wanted to die. It embodies the inhumane situation faced by Palestinians. Sakir Khader: “Jewish settlements have been built in the West Bank since the Nakba in 1948. Every time, Israel talks about a so-called two-state solution. But what should we accept if, in that possible second state, the lives of Palestinians are rendered completely impossible? All the territory is occupied and controlled by settlers. The residents of the West Bank are prisoners in their own land. They live like birds in a cage. Palestinians cannot fly anywhere. Gaza is hermetically sealed, and in the West Bank, there are many little Gazas, closed enclaves where you are checked if you wish to enter or exit. The Israelis maintain an enemy in the face of the world and then rightfully fight it. They speak of the vengeful Arabs, but who made them vengeful? Through this framing, they dehumanise the Palestinians, and as a counterpart, I want to give them a human face.”

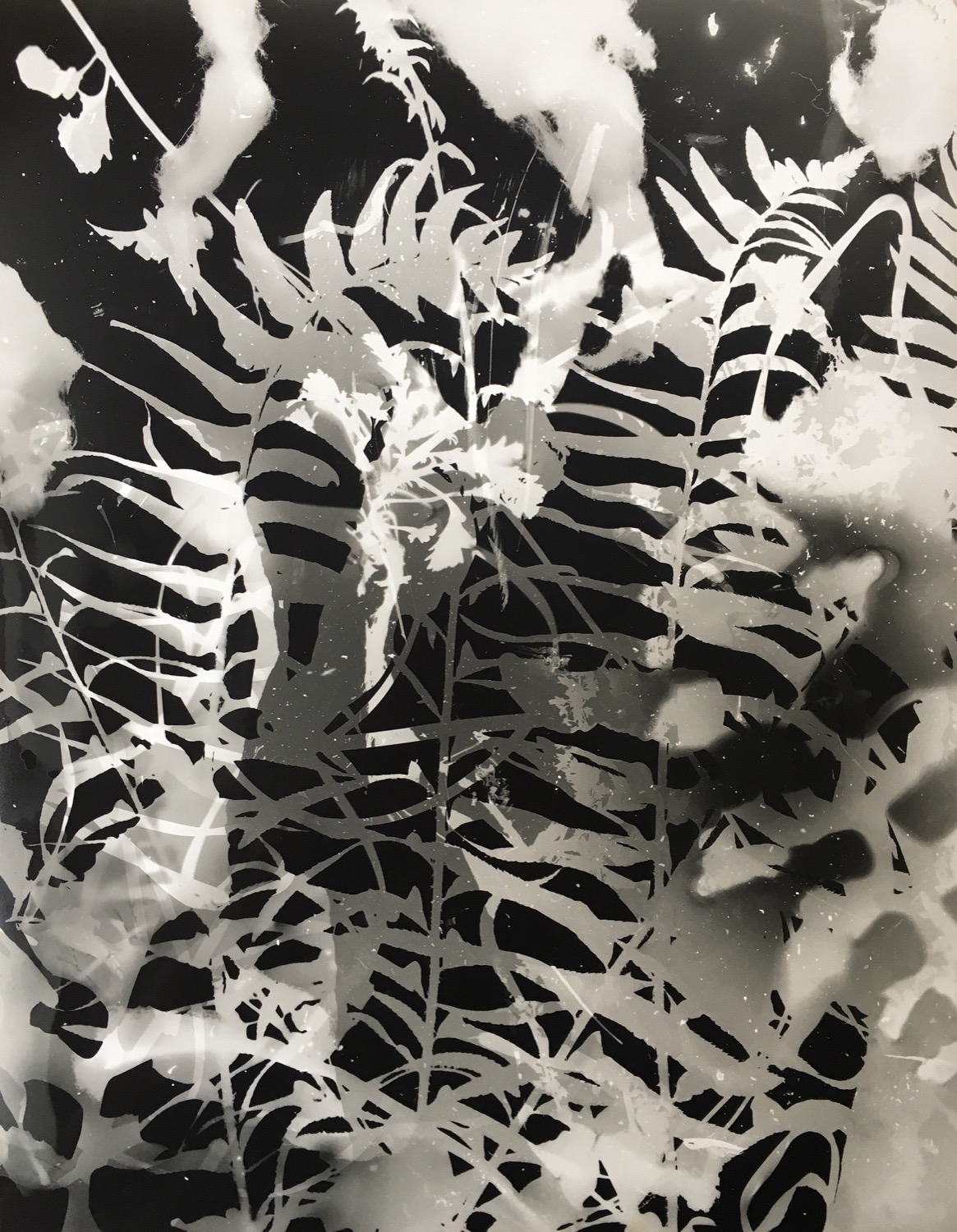

Power of beauty

Khader's photographs are aesthetically beautiful, which creates a tension with the tragic subject matter. This is an enduring dilemma that haunts documentary photography. The recently deceased grand master of photography, Sebastião Salgado, was often criticised for inappropriate aesthetics in his photographs of human suffering. This misguided accusation of ‘dramatic beauty’ could be viewed as hypocritical, as if beauty should only be allocated to the carefree aspects of life. Khader: “There is strength and beauty in misery. We are not weak victims. I show people with pride. I don't photograph Palestinians the way people used to photograph the pathetic children with fat bellies in Africa. The beauty in my images is the metaphor for human strength. The region where I work is a paradise. The deep wounds in paradise are reflected in my work, sometimes literally in the photos, but also in people's eyes. My responsibility is not only to portray pathetic people, but also to show them as resilient and powerful. I show the raw reality, but therein lies the strength and beauty.”

They will always be remembered through my photographs as people who lived and loved, rather than just numbers in an archive, without knowing their faces.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)