Dignified human statues in the desert

Nick Brandt

His most recent chapter, The Echo of Our Voices, turns to human subjects, portraying Syrian refugees in the Jordanian desert.

Artdoc

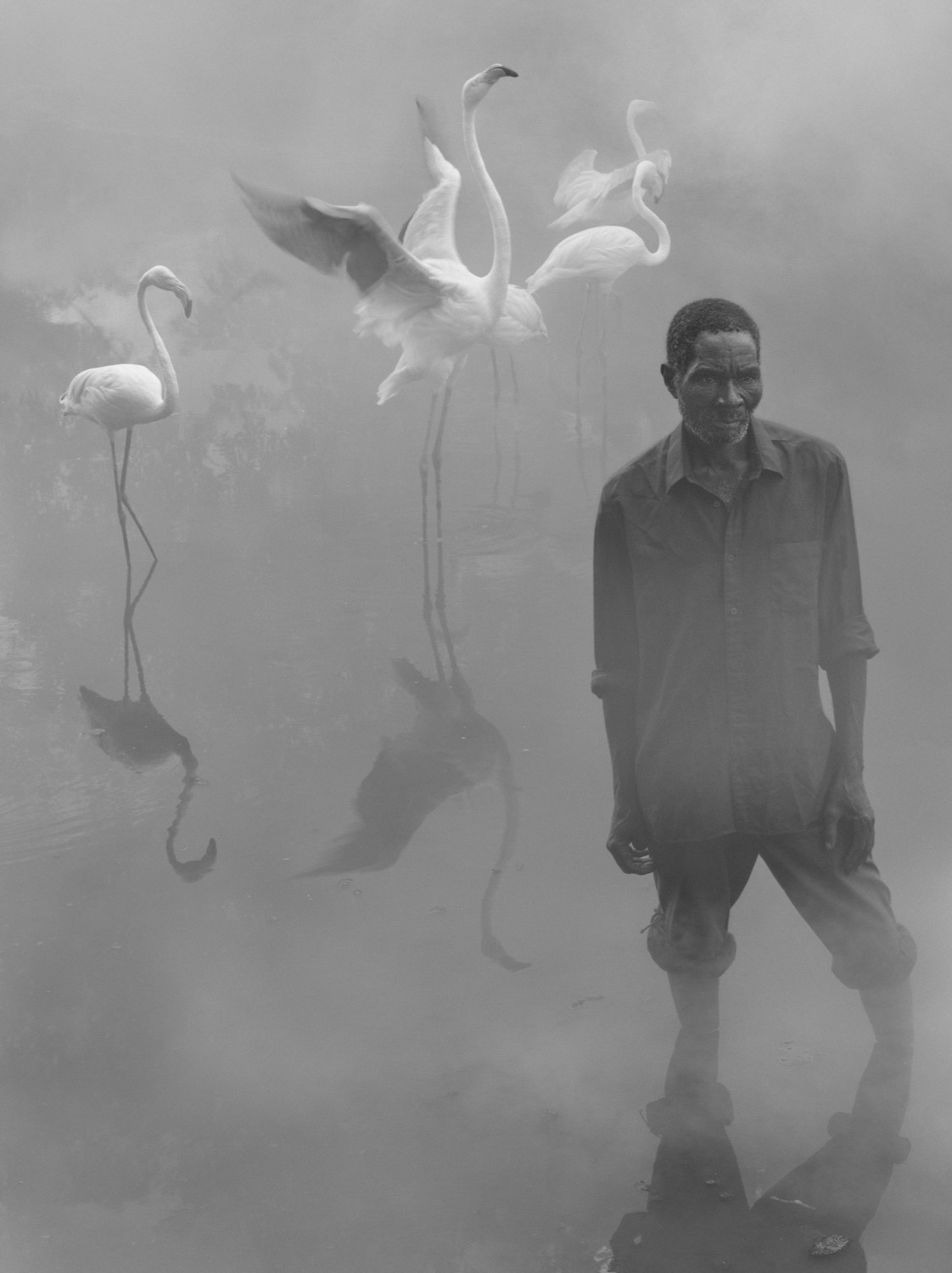

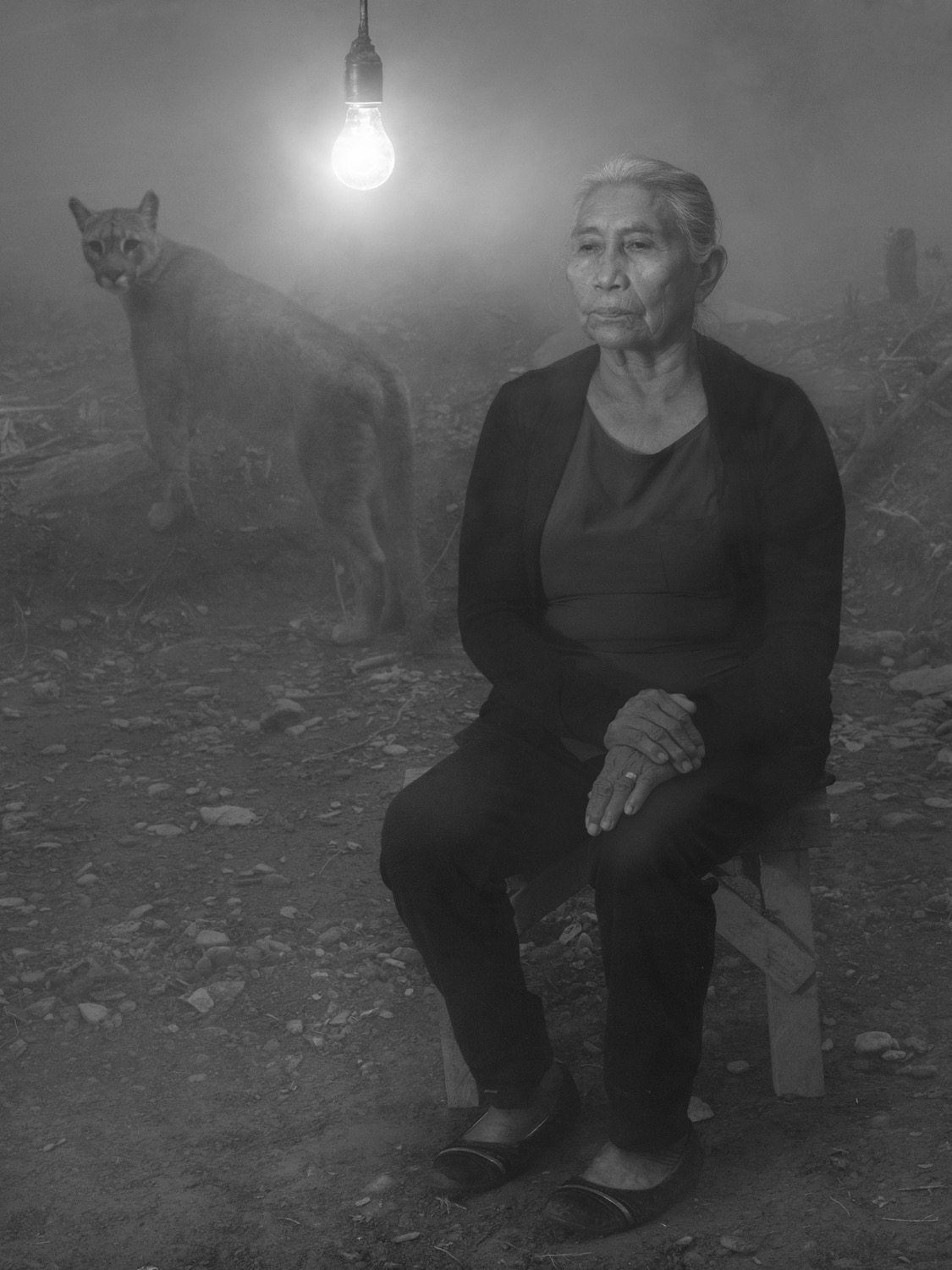

He was famous for his portraits of wild animals, like elephants, giraffes, leopards and lions in Africa, published in the trilogy On This Earth, A Shadow Falls and Across The Ravaged Land (2001-2012). Hereafter, he produced the series Inherit the Dust (2016) and This Empty World (2019), in which his concern about the escalating destruction of the East African natural world became apparent. For the last five years, photographer Nick Brandt has turned his lens towards the shared fate of animals and human beings in his ongoing series The Day May Break. Instead of making photojournalistic images of animals and humans, Brandt decided to create partly staged and partly spontaneous dramatic scenes. The most recent chapter, The Echo of Our Voices, shows Syrian refugees in the Jordan desert. “I wouldn't be taking these photographs if I felt there was no hope. I wanted to show the resilience of these extraordinary Syrian families.”

Payment Failed

Despite the success of his early work, Nick Brandt is not charmed if he is viewed through the prism of the On This Earth trilogy because, according to him, it has little to do with his work of the last decade. Often this early work was referred to as wildlife photography, but Brandt corrects that label. “Wildlife photography is a genre that is associated with a certain type of telephoto action photography. What I was trying to do was take portraits of animals in the wild as sentient creatures, no different from us. And I was waiting for them to present themselves for their portrait, just as Irving Penn or Richard Avedon were waiting in their studios, while I was out in the wild.”

What I was trying to do was take portraits of animals in the wild as sentient creatures, no different from us.

In the third and final episode of this series, Brandt focused more on the dangers wild animals face. In Across the Ravaged Land, we see photos of rangers with tusks of killed elephants and petrified birds. “I wanted to engage more directly with the destruction of the planet and the environmental injustice.” This statement still applies to all his works after his early work. His need to express his concerns about life on earth more directly resulted in a drastic change in his photography, leading to the series Inherit the Dust (2015) and This Empty World (2019).

After the first two chapters of The Day May Break, photographed in Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Bolivia successively, Nick Brandt produced chapter three, SINK / RISE, which was photographed in Fiji in 2023. For this chapter, shot underwater creating bluish tones, he photographed islanders as representatives of those whose land will be lost by sea level rise, in impressively posed underwater scenes. The fourth and most recent chapter, titled The Echo of Our Voices, is being published this fall (2025).

Fog as a visual symbol

The concept of The Day May Break was conceived in the first year of the covid pandemic. The world seemed to undergo a dramatic shift towards disaster. Nick Brandt wanted to express his concerns about our destructive relationship with the natural world and began photographing in Zimbabwe and Kenya in 2020, followed by images taken in Bolivia in 2022. In sanctuaries and conservancies, he photographed rescued wild animals alongside local inhabitants whose lives had been dramatically impacted by climate change. The black-and-white photographs are characterised by a fog that enhances the dramatic scenes. The fog was created with fog machines to give a sense of disorientation and insecurity. “It was also a visual symbol of wildfires around the world and of the natural world rapidly vanishing from sight. In those first two chapters, you have the people impacted by climate change in the foreground and an animal in the background fading into obscurity. When I photographed smaller animals like birds and monkeys, I had no choice but to have the animal in the foreground. But it still was that fog showing that everything is obscured and the natural world is disappearing from view.”

Frame of reality

In these dramatic and compelling photographs, Nick Brandt depicts in one single frame of reality the shared fate of humans and animals, staying far away from Photoshop or AI image constructions. “I find it meaningful that the animals and humans share the same frame. I have no interest in combining people and animals from different frames in post-production. I love the serendipity, the magic, the accident that can hopefully occur in camera from incidents you don't expect. I could pre-script, previsualize, for example, to have a lion on the left of the frame and a person on the right, and combine it afterwards in Photoshop, but that is of no interest to me. In Chapter Two, you do have people in the same frame as dangerous animals like leopards and pumas. For those pictures, we placed a thick wall of glass between the two that you can't see, which enables me to photograph the two in the same frame at the same time.”

Choreography with statues

For the fourth chapter, The Echo of Our Voices, Nick Brandt photographed Syrian refugees in the desert of Jordan, one of the most water-scarce countries in the world. According to Brandt, this chapter differs from the first three chapters, both visually and emotionally. It is a display of connection and strength in the face of adversity. For these compelling photographs, he choreographed the refugees, all dressed in dark attire, on stacks of boxes in the middle of the harsh and dry environment. He carefully arranged them in nearly geometric forms and aimed to showcase their strong emotional bonds. “It took a little time for them to understand what we wanted to achieve. At the end of each session, anyone interested would come over and look through the camera to see what I had photographed. By day six, they knew exactly what we were doing. They would climb up onto the boxes and find their own connections.”

Hope and resilience

With this chapter, Nick Brandt aims to move away from the melancholy of the first three chapters. “I wouldn't be taking these photographs if I felt there was no hope. I wanted to show the resilience of these extraordinary Syrian families who have been through so much, who have been displaced by war when they fled Syria, and now are facing perpetual displacement because of climate change. They live in the second-driest country on the planet, forcing them to relocate their tents multiple times a year to areas with sufficient rainfall for agriculture. What holds them together through all of this is family and friendship. That was what I wanted to convey with the connection within the photographs.”

The Syrian people display their calm and assertive faces in the photographs. These human statues act as symbols of strength and hope. The dark clothing was chosen for aesthetic reasons. “In black and white, the dark clothing creates graphic shapes within the landscape. We asked everyone to bring their dark clothes. All the women wear this style. The men sometimes dress in Western clothes, sometimes in traditional attire."

Because of the harsh daylight of the desert, the people in the picture are highlighted by artificial light. For almost every photograph, Brandt used a 12K HMI light on a lighting stand. “We always photographed backlit or three-quarter back-lit by the sun so that the mountain ranges in the background are in silhouette. This light filled in the shadows so you can see their faces.”

Staged reality and serendipity

The power of photography, even in staged work, lies in the direct connection to the real moment, to the lived reality without digital enhancement. Nick Brandt's work has gradually shifted from a purely documentary, almost journalistic approach, to a more artistic vision in which his personal interpretation is strongly evident. Experimenting with new ways of photographing is inherent in his practice. “Each time, I want to do something that I have not seen before. And with that comes the challenge of how to execute that creatively. There's a healthy kind of fear involved, of how am I going to achieve this? I could have saved a great deal of money and time if I had loaded a truck with boxes and driven to where the Syrian families were living in their tents, where I could have photographed them. Then I wouldn't have had this meaningful desert backdrop. The mountains echo the shapes of the human statues. The desert acts as a symbol of the increasing desiccation of the planet.”

Although meticulous staging plays a crucial role in these photographs, serendipity and accident also play a significant part. “I continue to embrace more and more accidents. And when you look at these photographs of The Echo of Our Voices, you see them choreographed with what appears to be an inch of their life. Every hand has been turned with care. Every finger has been analysed. I couldn't have done this on my own. I worked with two creative collaborators who focused on the choreography. But within that staging, there are still accidents that happen that make the photograph work. For the photograph Women with Sleeping Children, we had two more children on the boxes, and during the shoot, it was getting cold. Once the sun sets in the desert in March, it's bloody cold, and the kids were freezing. We let the two children who were cold go back to the tent, and suddenly, the negative space of the boxes opened up spaces that gave the choreography on the boxes in a much more balanced way.”

Photography as expression

Even though these aesthetically excellent and ethically strong photographs, asking the audience for greater care for the earth’s environment and for vulnerable people, Nick Brandt does not consider himself an activist whose main aim is to change the world. “I have always created purely for myself, not thinking about a photograph during the shooting in terms of how people will be affected or motivated or enlightened by this work. Hopefully, along the way, people will gain a deeper understanding of what these individuals and animals' lives are like. But obviously, the motivation comes from my anger at environmental injustice, and injustice just generally, and trying to find a way to express that through some, hopefully, original visual means.”

Jean-François Leroy, the director of Visa pour l'image, the International Festival of Photojournalism, wanted to exhibit The Day May Break because he felt that Brandt was a photojournalist, even though Brandt told him that he staged the photos. “I feel more affinity with photojournalists than I do with ‘fine art photographers’ because of the socio-political environmental concerns. However, I don’t like the labelling of genres and types of photography. I simply create work through photography. For me, the most important question should be: Does it move you?”

I wanted to engage more directly with the destruction of the planet and the environmental injustice.

About

Nick Brandt was born and raised in London, where he initially studied Painting and Film. He has lived in the southern Californian mountains for most of his adult life. However, as of 2025, with the dystopian hellscape that America has become under Trump and his horror show goons, he will be moving to Portugal. The themes in Nick Brandt’s work always relate to the destructive impact that humankind is having on both the natural world and humans themselves. Brandt has had solo gallery and museum shows around the world, including New York, London, Berlin, Stockholm, Paris, and Los Angeles. In 2010, Brandt co-founded Big Life Foundation, a non-profit in Kenya/ Tanzania that employs more than 350 local rangers protecting 1.6 million acres of the Amboseli/Kilimanjaro ecosystem.

The Day may Break will be exhibited in Hangar, 18 Place du Châtelain, Ixelles, Brussels, 1050 Belgium, 19 September - 21 December 2025.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)