Migration Without Departure

Oscar Villeda

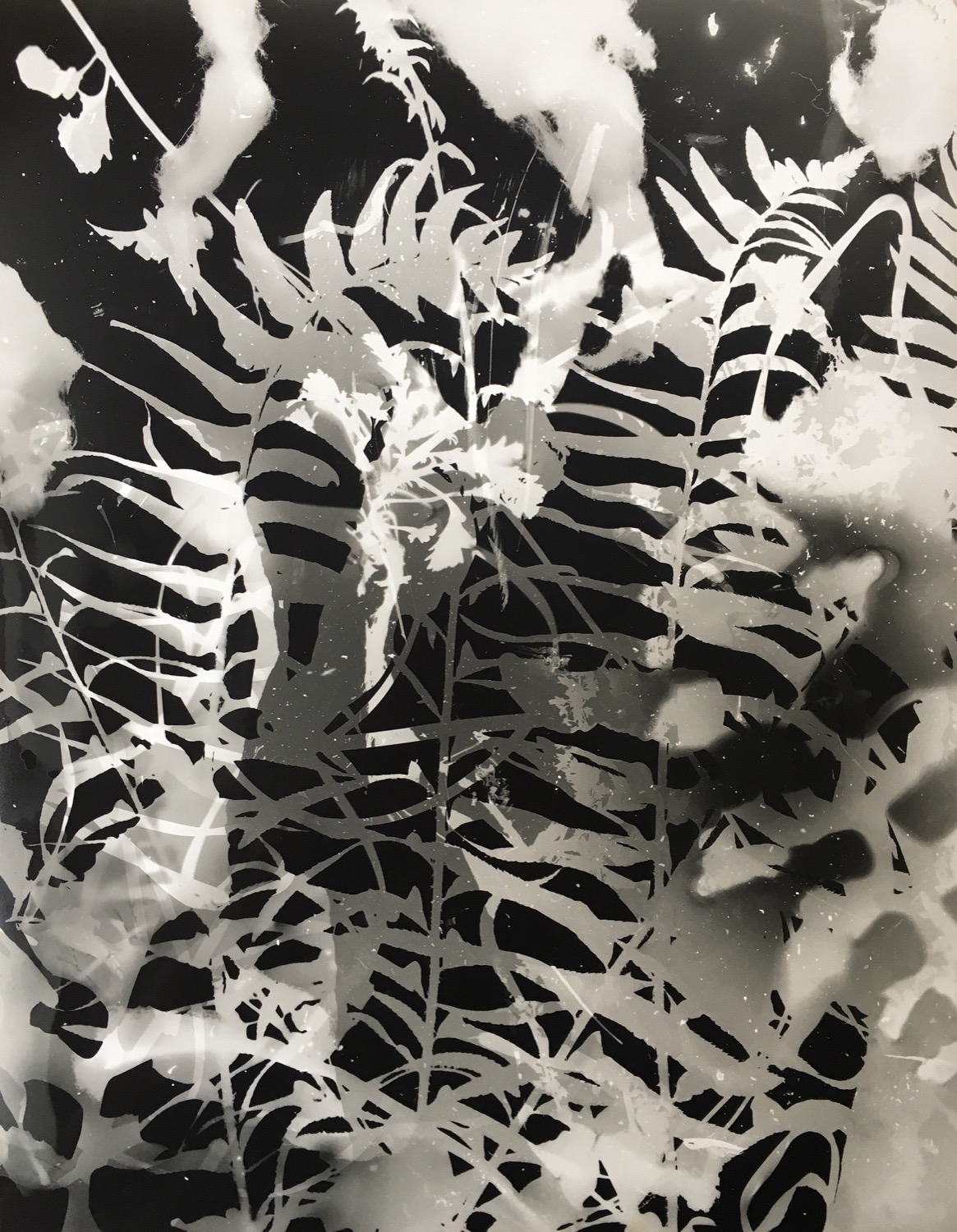

Oscar Villeda’s Tu pueblo sabe honours Maya Mam resilience, migration, and memory.

Artdoc

High in the Cuchumatanes mountains, where the streets of Todos Santos Cuchumatán carry the weight of journeys taken and those yet to come, Oscar Villeda has shaped a photographic language grounded in belonging. His photographs hold both absence and presence, capturing the tender spaces where family, memory, and migration meet. At the centre of this practice stands Tu pueblo sabe, a long-term project that honours the resilience of a Maya Mam community and the affections that travel with its people. His images linger on the symbols and iconography of the United States, used and redefined within the Maya village. "This transformation of the local imagery is the result of the efforts of men and women looking to achieve the modernity that they could not find within their borders."

Payment Failed

In 2022, Villeda began Tu pueblo sabe, a project set in Todos Santos Cuchumatán, a Maya Mam community high in the Cuchumatanes mountains. The project explores how family stories, affections, and memory migrate alongside—or in place of—people. While migration stories often follow a journey outward, this one remains firmly in place. Here, the traces of departure are everywhere: boys in crisp baseball caps and sneakers with American logos; the local cemetery with graves decorated in stripes and stars; houses with bright façades bearing the quiet imprint of relatives working far away, in hopes of finding better opportunities. "The people of Todos Santos show great versatility in taking symbols and iconography from the United States, reinterpreting and using them in this new context as a narrative tool to tell their own story of migration," Villeda explains. "It's a way to pay homage to the land of opportunities or connect with relatives who braved the trip north looking for a better life."

The people of Todos Santos show great versatility in taking symbols and iconography from the United States.

Transnational Families

Todos Santos Cuchumatán is home to more than 30,000 people, the vast majority Maya Mam. Shaped by a long history of inequality and limited opportunities, the community has seen many of its members leave for the United States, creating far-reaching family and cultural networks that stretch across borders. These connections are sustained through remittances, shared celebrations, and a distinctive "architecture without architects" – brightly built homes designed through collaboration between relatives abroad and those who remain. "One of the effects of migration is the emergence of transnational families, which, when fragmented by time and space, resort to various methods that allow them to maintain emotional, social, and economic bonds," Villeda explains. "These often materialise in exchanges in the form of economic and cultural remittances, gifts, photographs, phone calls, and even, when travelling from one country to another is possible, visits. The nuances of the transnational condition are also found in the absence and loss of loved ones. The correct functioning of family ties in this space depends on the quality of family networks and the capacity for communication that exists among its members."

Personal Memories

For Villeda, Tu pueblo sabe is inseparable from his own memories. "The act of taking photos feels like small moments and memories throughout my life," he says. "My father worked for many years in the development sector, supporting vulnerable families in rural Guatemala, and he used to take me along on many of his field visits when I was a kid. My mother taught me to look at the world with wonder."

He first studied communications, drawn to video before discovering photography. "It wasn't hard to let go of video. My grandfather is a photographer, and that closeness to the craft made the process much more accessible. Now, as a husband and father—among many other things—I’ve learned to look inward and allow the story I’m trying to discover also to reveal its tenderness, intimacy, and candour. By searching within myself first, I hope these elements are present in the photographs as well, creating an emotional tone that comes from within.”

Photography as Accompaniment

"I believe photography remains a powerful form of communication—despite its limitations and paradoxes," Villeda says. "There are countless historical examples of how photographers' work has not only brought attention to specific issues but also shaped how we see the world, our relationship with it, and even how we see ourselves. Images help shape the ideas we form about any topic or group of people—and the stories we tell ourselves."

Images help shape the ideas we form about any topic or group of people—and the stories we tell ourselves.

He is careful to draw a line between representing and speaking for others. "As a photographer, I speak only for myself—especially when dealing with social issues and longstanding inequalities. In my country, there is a lot of that. Many vulnerable communities have been telling their own stories and sharing their struggles for years—it's just that, in many cases, there are no platforms for their voices to be heard. At the very least, I try to make my work a tool to acknowledge the stories of others and help them reach new 'ears'."

For Villeda, the role is not to claim a voice but to walk alongside it. "My role is not to speak for anyone but to respectfully accompany the process of telling and recognising ourselves in the stories around us, even as we acknowledge the differences. I hope my images spark more questions and, perhaps through the need to answer them, inspire others to find ways to get closer and open themselves up to different truths."

A Grounded Visual Language

To convey family stories, affections, and memories, Villeda wanted the photographs to feel close and grounded. "I thought one way to do this was to eliminate the 'filters' that photographic technique sometimes creates between the viewer and the image, and I wanted the photos to feel 'normal'." He used a single 40mm lens for the entire project, a choice he has maintained since 2019. "That consistent practice helped me find a language that fit how I wanted the story to feel. I also tried to include elements from vernacular photography so that my images could echo family albums and framed pictures hanging on the walls of the homes I visited."

In Tu pueblo sabe, much of the work began with walking through the streets and into the mountains of Todos Santos Cuchumatán. "That walking was essential to discovering the stories I eventually learned from. I think my photographs—not just in this project but in general—tend to carry a 'wandering around' quality to them." His approach is also shaped by a close study of other artists. "While working on Tu pueblo sabe, I kept on feeling especially inspired by the way photographers like Juanita Escobar and Erika Larsen can elevate the everyday into something mystical."

Curiosity for Human Experience

For Villeda, curiosity is the starting point of every image. "I always respond to whatever sparks my curiosity. In that sense, photography is a method of learning, understanding, and approaching, while also being a means to share what I've learned. I choose themes and subjects that allow me to explore and get closer to ideas I'm discovering. I believe that wherever we go, and with whomever we share space, there's always a story waiting to be discovered if we open ourselves to let it speak and reveal itself." For Villeda, storytelling is a way to synthesise the experiences he gains through photography. “I try to find the thread of meaning that gives a deeper sense to what people tell me, to the places they inhabit, the interactions between the two, and my relationship to it all.”

In Oscar Villeda's photographs, human connection is never an afterthought—it is the pulse that carries each image. His work emerges from a deep curiosity about how others live, dream, and endure, and from a belief that our shared existence can either fragment or unite us. "I've always been curious about how other people carry their own human experience," he reflects. "Beyond understanding their desires, fears, joys, and pains, I've always been drawn to the idea that simply being alive and sharing this planet can either divide us—when we let it—or connect us and remind us that we are not alone."

About

Oscar Villeda was born in Guatemala City, where he currently lives with his wife, son, and dog. He discovered photography while studying Communications at Universidad Rafael Landívar, graduating in 2012, and later earned a master's degree in Strategic Design and Innovation. He has worked in the field of international cooperation, addressing issues such as education, poverty, and migration. His experience includes development projects with vulnerable communities, particularly Indigenous youth from Guatemala's Western Highlands. Much of his photographic work grows out of this background. However, he has also contributed to a wide range of stories as a photographer for national outlets including La Hora, Siglo XXI, Esquisses, and Plaza Pública, as well as international publications such as taz, The New Humanitarian, Guernica, and Asymptote. Since 2015, Villeda has taught photography at several universities across Guatemala. He also organises and hosts a quarterly photography salon, fostering a community of learning, creation, and reflection.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)