The resistance of past enslaved communities

Nicola Lo Calzo

Nicola Lo Calzo documents postcolonial memory and legacy among slavery’s descendants.

Artdoc

Historians generally estimate that between the mid-15th century and the late 19th century, approximately 11 to 12 million African men, women, and children were forcibly transported across the Atlantic into slavery in the Americas. Torn from their homelands, they endured brutal voyages and enslavement, shaping the economic, cultural, and demographic history of the Americas for centuries to come. Since the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, the descendants of those once enslaved still grapple with their inherited past. Now living in West Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas, they foster resistance against postcolonial prejudices and find ways to cope with their brutal history. In his extensive project, Nicola Lo Calzo, an Italian and Paris-based queer photographer and researcher, explores the complexity of the visible and hidden memories of postcolonial descendants, along with their strong and vital resilience.

Payment Failed

As a queer person, Lo Calzo felt a resonance with his own experience, which fuelled his interest in how Afro-descendant communities developed strategies of resistance. “How can they produce spaces of self-affirmation, spaces of self-determination against colonialism, against slavery, against oppression? This idea of refuge within or beyond a dominant system was also part of my own experience in a different way. I truly believe that there is a resonance between the ‘queer’ - in the phenomenological sense of the term, as an experience that is disoriented and not aligned with the norm - experience and that of the maroon people: both involve escaping systems of control and oppression, and creating spaces of survival, resistance, and reinvention outside the boundaries of the Norm. The connection is the act of escaping as an act of creating oneself.”

His sense of identity naturally led him to focus on these resistance practices and to gain acceptance among other minorities. “I was welcomed in various sacred spaces where this legacy of resistance to slavery is passed down through generations. In many cases, some queer people opened the doors for me and allowed me to enter these different worlds. It is not by chance that Afro-descendant practices, like Voodoo in Haiti, Candomblé in Brazil, or Tchamba vaudou in Togo, still serve as spaces of freedom for queer individuals today: these spaces are not organised according to the normative lines of society like race, gender and class, but exclusively according to the will of the Lwa divinities.”

Relation to the past

For minority groups, especially the descendants of enslaved persons, their relationship with the past is vital because it helps them forge an identity that was stolen by the dominant system. Lo Calzo explains the importance of revisiting the past. “For them, it is important to bring back the past through their practices because it's a way to build a contemporary identity in front of a society that is not always welcoming. For subaltern communities, the discovery of the past is a guarantee of historicity and, therefore, of humanity. It's a strategy to face the dehumanisation of the dominant groups. The communities of descendants reenact the past, transforming and reformulating it. The contemporary practices create a new, transformative relation with the past. Their rituals actively shape their memories of the past and produce a counter-narrative.”

Nicola Lo Calzo photographs the rituals and celebrations within communities, allowing him to portray not just an outsider’s view but the lived experience of local people. “I still remain an ‘outsider’, but I try to shape my gaze in a situated way. After all, as a queer person, the possibilities of being an ‘insider’ are very limited. My perspective was shaped in a horizontal way. I have to thank my parents certainly, but paradoxically also the system. As a queer person, I was raised not only with my own gaze but also under the gaze of others. This double consciousness has given me a certain sensitivity when engaging closely with people. Moreover, I believe there are other reasons—such as my peasant roots rather than a bourgeois background—that make it easier for me to connect with rural and working-class communities, like those I have often photographed.

I need to spend much time with the communities, it’s the only way to develop my vision, aesthetic and ethical.

Through his images, he aims to capture the enigmatic complexities of practices rooted in local histories. He seeks to create an image from within, rather than from an outsider’s perspective. “I try to make a representation of these practices with a critical and situated gaze. That's why I often work closely with the communities. It's a way to deconstruct my gaze. For me, it is essential to understand the gaze of the people I am photographing, and to let their gaze influence me.” Lo Calzo’s approach explains the longevity of his long-term project. “I need to spend much time with the communities, it's the only way to develop my vision, aesthetic and ethical.”

The body archive

His work's primary aim is to depict the community’s life and its connection to the past, which is also rooted in a specific relation to space, geography, and territory. Only later did the political aspect emerge. “The political, to me, is to choose to focus on topics that are usually overlooked or not very visible in the media, as well as in contemporary art or photography. When I began this work 15 years ago, it was very difficult to approach a magazine and explain why I was working on resistance to slavery. The magazines were unaware of the subject. I needed to clarify the history and geography of slavery and its resistances. Defending my work on slavery and colonialism resistance is a political act for me.” The history of slavery is mainly written by colonial powers themselves, often leaving out themes like resistance and the struggle experienced by the enslaved. “Our knowledge is shaped by the official history with a focus on written archives. Most of the time, the perspective is that of the colonisers. It is not from the point of view of communities or their descendants. While I am working to rewrite this history by focusing on a different archive, what I call the ‘Body Archive’, most of these memories are rooted in the bodies of the people I photograph. When working with a community, you can gain their perspective on the same history. This helps to deconstruct the traditional memory of slavery and highlights resistance from the people's point of view. Consequently, I undertake extensive oral investigations because their ceremonies encompass intangible heritage.

Writing is a fundamental aspect of Lo Calzo’s photographic research. “That's why I also decided to pursue a PhD, because it was important to emphasise this connection between photography and research on ethnology, as well as queer studies, black studies, sociology, and feminist studies. I have just completed a PhD in Arts, with a Practice-Led Research focus in photography.”

The name Kam

The project Kam was originally called Cham, but Lo Calzo changed the name in order to add a new meaning. ‘Cham’ was a name that appeared to refer to sub-Saharan peoples in the Old Testament and was used at the beginning of Modernity to justify racist opinions. “It was the way through the European countries with the Catholic Church, legitimising the slave trade, transportation, and colonisation. Cham is a distortion of the original word ‘Kam’, a term that was reappropriated in the '60s by the Senegalese historian and anti-colonial activist, Cheikh Anta Diop, to highlight the antiquity of African civilisations. Kam is an ancient Egyptian word referring to sub-Saharan peoples, without racial connotations. I chose to use this word as the title for my project. It was also a way for me to pay tribute to Anta Diop and his legacy.” The seemingly simple word reflects Lo Calzo’s awareness of subtle meanings, with the careful choice of this title revealing a deeper significance.

At the end of his major project, Nicola Lo Calzo plans to publish a final book that will include all the images and investigations. “I need to make a point on these 15 years of work with the book, but I think that we'll never finish this project.”

Poetic Documentary

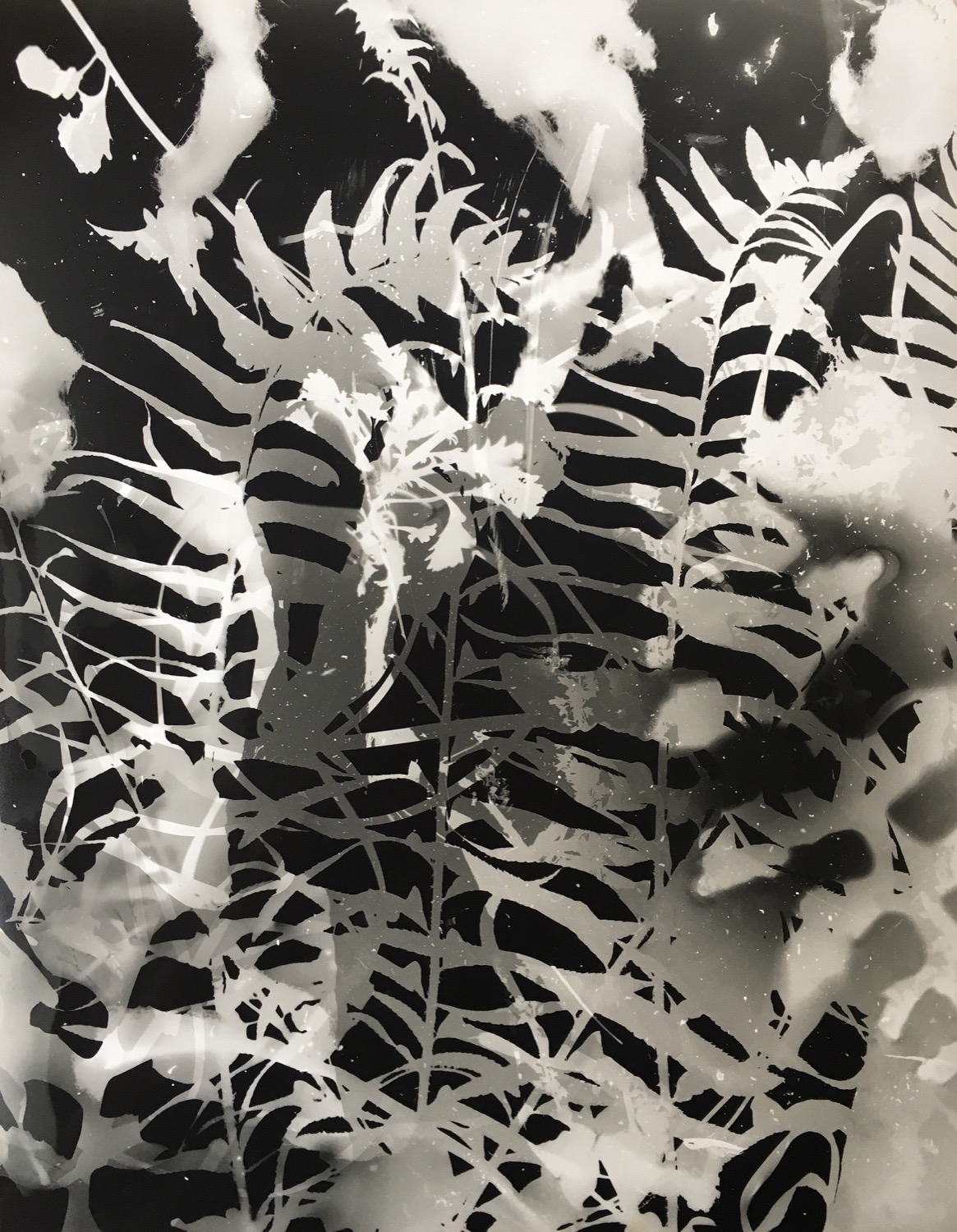

The photographs of Lo Calzo demonstrate a personal yet universal approach, rooted in a documentary style, full of vibrancy and colour. As a viewer, you experience the lived realities of the local people and their resilience. “The aesthetics of my work depend on the people and places I have photographed. There are works, such as those I did in Suriname and French Guiana with the Bushinenge community, where I tried to incorporate the specific use of colours of this community. “I try to reproduce their use of colour, which is very saturated and flowing. At the same time, I aim to highlight the rich chromatic palette of the forest and the unique aesthetics that emerge from the profound relationship between Bushinengue culture and the forest environment. In other cases, for example, when I worked in Ghana, at the beginning of this project, I was closer to a more "classic" vision of photography. I used to work in a more structured manner, maintaining a certain distance from the subject and paying close attention to composition. As an architect, I’ve always had a natural obsession with lines and forms. Over time, however, I went through a process of emancipation. If you look at my recent work, you can notice this shift, a move away from the architectural structure that initially influenced my gaze, towards a more organic and intuitive vision.”

In his photographs, viewers can discern certain enigmatic symbols, like shadows on the ground or necklaces with hidden meanings. Lo Calzo's work is both documentary and poetic. “I don't want to be too literal. I like to keep opacity in my photography because the practices I photograph also have a regime of opacity. You can only show what is permitted to be shown. This opacity respects the soul of these practices, which were raised into secrecy. It is also an aesthetic strategy. It provokes reflection and thought. The poetry in my work is fundamental. I craft my own very personal mythology around these different stories.”

Identity

Lo Calzo emphasises the distinction between building identities and adopting a critical perspective. “It's crucial to valorise the critical point of view from different experiences and not to reduce a person's stance to an identity, because identities are static. They are a trap, a closed space. When we talk about queerness or blackness, it should no longer be necessary to use these categories to think of ‘the Otherness’. The prevailing approach in the art world is to think in terms of identity, rather than through the notion of critical stance. The word ‘slave’ is an example of a false identity. Now we use ‘enslaved’, which means the individual was brought into slavery. This is important because this word does not diminish the person's humanity. With this word, you acknowledge that the person was originally a free man.

For me, it is essential to understand the gaze of the people I am photographing, and to let their gaze influence me.

About

Nicola Lo Calzo is a photographer and teacher-researcher based in France since 2006. He currently works in Paris where he runs a course on anticolonial and queer practices in photography at the École Nationale Supérieure d'Arts de Paris-Cergy and Sciences Po Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Lo Calzo is the recipient of Strategia Fotografia Grant (2023), Bnf Grande Commande Photographique (2022), Cnap Grant (2018), nominated for the Prix Elysée (2019) and the Niépce prize (2020). In 2023, he is a founder member of the editorial committee of the digital arts research platform PLARA and collaborate, as guest curator, to the 8th edition of the International Biennial of Photographic Encounters of Guyana.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)